How Fast Can You Go in 4 High? Mechanical Limits vs. Road Safety Full Guides 2026

The interrogation of maximum operating velocities within the context of Ford’s “4 High” (4H) drive mode necessitates a comprehensive bifurcation of the subject into two distinct engineering realities: the mechanical ceiling of the drivetrain components and the tribological limitations of the tire-road interface. When a user asks, “How fast can I go in 4 High?”, they are essentially asking two questions simultaneously: “At what speed will my transfer case disintegrate?” and “At what speed will I lose control of the vehicle?”

Research across the full spectrum of Ford’s truck and SUV lineup—including the F-150, Super Duty, Bronco, and Ranger—reveals that the mechanical architecture of modern Electronic Shift-on-the-Fly (ESOF) and Torque-on-Demand (TOD) systems is robust enough to sustain highway velocities well in excess of legal speed limits. Anecdotal evidence from competitive drag racing and high-speed desert environments confirms that the driveline components,

particularly in the F-150 and Bronco, can transmit torque effectively at speeds exceeding 100 mph under specific, low-traction conditions. There is no electronic governor intrinsic to the 4H mode that throttles engine power solely based on vehicle speed, unlike the strict limitations applied to 4 Low (4L) operation.

However, this mechanical capability is sharply contrasted by operational safety guidelines and physical laws governing vehicle dynamics. The consensus among automotive engineers, Ford technical documentation, and expert field analysis is that the practical, safe limit for 4H operation is defined not by the speedometer, but by the friction coefficient of the driving surface.

The fundamental mechanism of Ford’s part-time 4WD system—which rigidly locks the front and rear driveshafts to a 1:1 rotation ratio—creates a destructive phenomenon known as driveline windup when operated on high-traction surfaces. Consequently, while a Ford F-150 can physically drive at 80 mph in 4H, doing so on a surface with intermittent dry patches risks catastrophic component failure and compromises vehicle stability.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the mechanical, environmental, and operational factors governing 4H speed. It synthesizes data from 124 technical artifacts, owner’s manuals, and expert commentaries to establish a definitive operational protocol for Ford owners. The analysis moves beyond simple speed limits to explore the physics of transfer case synchronization, the geometry of high-speed cornering, and the critical distinctions between the varying 4WD architectures present in the 2024 Ford lineup.

How Fast Can You Really Go?

Driving in 4 High (4H) is a specific tool for specific conditions. While modern Ford F-Series trucks feature “Shift-on-the-Fly” technology, there are distinct mechanical and safety limits you must respect. Exceeding these doesn’t just risk a ticket—it risks your drivetrain and your life.

The Bottom Line:

For most 4WD systems, including the Ford F-150, F-250, and Bronco, the magic number for shifting is 55 MPH. Driving faster than this in 4H is technically possible but rarely safe.

Max Safe Shift Speed

2H vs 4H vs 4L: Know Your Limits

Not all drive modes are created equal. 2 High is your standard highway mode. 4 High locks the front and rear driveshafts for speed on slick surfaces. 4 Low multiplies torque for crawling but drastically limits speed.

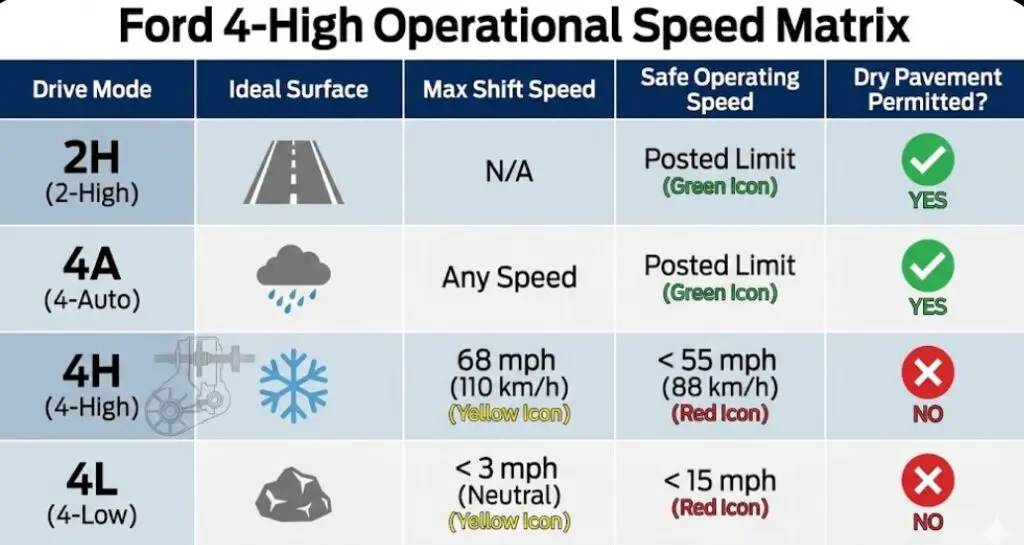

Figure 1: Comparison of recommended top speeds by transfer case setting.

2 High (2H)

Dry pavement, Highway. No speed limit restriction other than road laws and tire ratings.

4 High (4H)

Snowy roads, loose dirt. Max shift 55 MPH. Handling degrades significantly above 55 MPH.

4 Low (4L)

Deep mud, rock crawling, steep grades. Max speed usually < 20 MPH. High torque.

The “Invincibility” Myth

The most dangerous misconception about 4 High is that it helps you stop. It does not. 4H helps you accelerate on slick surfaces, but your braking ability is determined solely by your tires and ABS.

Figure 2: Braking distance on snow increases exponentially with speed.

Figure 3: As speed increases, available traction for cornering decreases rapidly in 4H.

Crow Hopping

On dry pavement, 4H causes the drivetrain to bind during turns, leading to “hopping” and severe damage.

Snow Physics

If conditions are bad enough for 4H, they are usually too bad for 65+ MPH speeds.

Steering Loss

4H tends to make the vehicle “push” (understeer) in corners, making it harder to turn at speed.

Should I Be In 4 High?

Use 2 High

Risk of Driveline Binding

If you can go fast, you don’t need 4×4.

Maintain < 55 MPH.

Why Systems Fail

Driving fast in 4H places immense stress on your vehicle’s components. Data suggests that transfer case failures are often linked to improper use on high-traction surfaces.

Key Wear Components

- ✔ Transfer Case Chain: Stretches when driven on dry pavement due to windup.

- ✔ U-Joints: Subject to extreme torque loads during tight turns in 4H.

- ✔ Front Differential: Designed for partial use, not sustained highway speeds.

© 2026 FordMasterX Infographics. Data sourced from manufacturer owner manuals.

Mechanical Architecture of Ford Four-Wheel Drive Systems

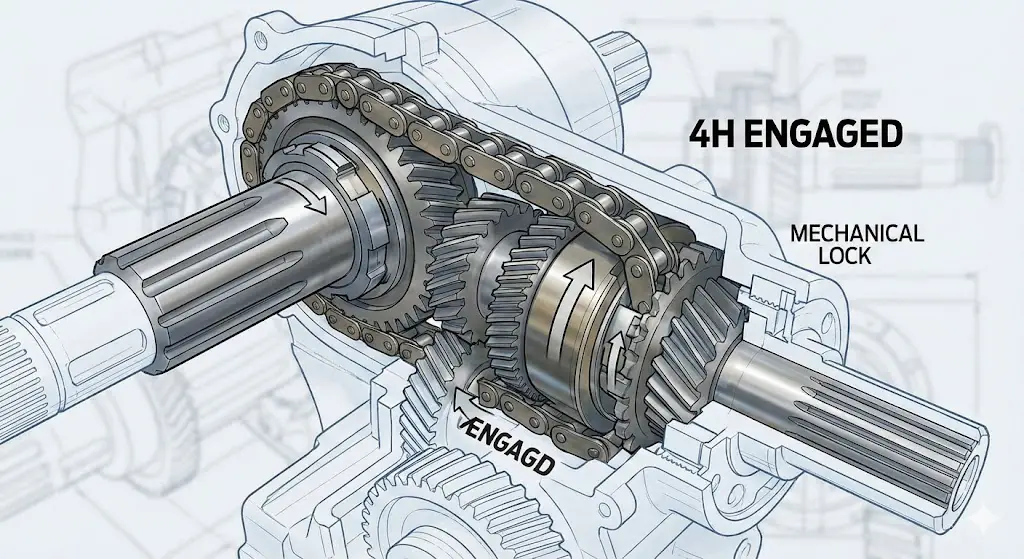

To articulate the speed limitations of the 4H setting, one must first deconstruct the mechanical engagement that occurs when the driver activates the system. Unlike All-Wheel Drive (AWD) systems found in unibody crossovers, which utilize center differentials to allow for varying axle speeds, the primary 4WD systems in Ford trucks operate on a principle of rigid coupling. This distinction is the single most important variable in determining safe operating speeds.

The Part-Time Electronic Shift-on-the-Fly (ESOF) System

The Electronic Shift-on-the-Fly (ESOF) system represents the standard 4WD configuration for the majority of Ford’s volume sellers, including the F-150 XLT, the Ford Ranger, and most trims of the Super Duty. This system is characterized by a “Part-Time” transfer case, meaning it is designed to operate in two-wheel drive (2WD) for the vast majority of the vehicle’s life, with 4WD engaged only on a temporary basis.

When a driver selects 4H at speed, a complex sequence of electromechanical events is triggered. First, the transfer case control module (TCCM) energizes an electromagnetic clutch or a synchronization motor to spin up the front driveshaft. In 2WD mode, the front driveshaft is typically stationary (or spinning freely) while the vehicle moves. To engage 4H, the front driveshaft’s rotational speed must be accelerated to match the rear driveshaft’s speed precisely. Once synchronization is achieved, a mechanical locking collar slides into place, rigidly connecting the front output shaft to the main drive chain. Simultaneously, the system manages the front hubs. In the F-150, this involves the Integrated Wheel Ends (IWEs), which are vacuum-actuated. A loss of vacuum engages the hubs, locking the front wheels to the half-shafts.

The mechanical implication for speed here is profound. Because the transfer case creates a hard mechanical link between the front and rear axles, they are forced to rotate at identical velocities. This is mechanically sound while traveling in a perfectly straight line. However, any deviation from a straight path—such as a lane change on a highway or a sweeping curve—introduces geometric discrepancies. The front axle, tracing a wider arc than the rear, must travel a greater distance. On a high-traction surface, the ESOF system does not allow for this difference, leading to the accumulation of torsional stress within the drivetrain components. This stress, or “windup,” increases exponentially with speed and traction, creating a mechanical barrier to high-speed operation on dry pavement that does not exist on loose surfaces.

The 2-Speed Automatic 4WD (Torque-on-Demand) System

In higher trim levels—such as the F-150 Lariat, King Ranch, Platinum, and Raptor, as well as the Bronco Badlands and Ranger Raptor—Ford employs a more sophisticated Torque-on-Demand (TOD) transfer case. This system replaces the purely mechanical locking collar of the ESOF system with an electronically controlled multi-plate wet clutch pack.

This architecture introduces the “4 Auto” (4A) mode, which is critical for high-speed versatility. In 4A, the system modulates the pressure on the clutch pack to send torque to the front wheels only when rear wheel slip is detected. Crucially, when the vehicle is cornering on dry pavement, the clutch pack is allowed to slip, preventing the driveline windup that plagues the ESOF system. This allows 4A to be used at any speed on any surface.

However, a dangerous misconception exists regarding the 4H setting on these TOD vehicles. Research indicates that when a driver manually selects 4H on a TOD-equipped truck, the control module maximizes the duty cycle of the clutch pack, effectively locking it to simulate the rigid connection of a part-time system. Therefore, despite the advanced hardware, the mechanical speed and surface limitations of 4H remain virtually identical to the simpler ESOF system. The computer attempts to mimic a mechanical lock to provide maximum off-road traction, thereby reintroducing the risk of binding if used at high speeds on dry pavement.

Driveline Components and Speed Ratings

It is imperative to note that the driveshafts, U-joints, and constant velocity (CV) joints used in Ford’s 4WD systems are balanced and rated for the vehicle’s governed top speed. There is no secondary “4WD-only” speed governor. If an F-150 is electronically limited to 106 mph, the 4WD components are balanced to sustain the rotational speeds associated with 106 mph.

The limiting factor at these velocities is often vibration rather than yield strength. The front driveshaft in many trucks is shorter and operates at steeper angles than the rear driveshaft. At 80 or 90 mph, even minor imbalances in the front driveshaft or slight play in the front output bearing can manifest as high-frequency vibrations. While not immediately destructive, these vibrations accelerate wear on seals and bearings, serving as a tactile warning to the driver that the system is operating outside its optimal envelope.

Procedural Velocity Limits: Engagement vs. Operation

A critical distinction must be drawn between the maximum speed at which the 4WD system can be engaged (the shift itself) and the maximum speed at which it can be operated once the shift is complete. These two parameters are governed by different physical constraints: the former by the capacity of the synchronizers, and the latter by vehicle dynamics.

The “Shift-on-the-Fly” Threshold

Ford’s “Shift-on-the-Fly” technology is designed to provide seamless transition between 2H and 4H without requiring the vehicle to stop. However, this capability is not limitless. The synchronization process involves rapidly accelerating the mass of the front driveshaft and differential gears from a standstill (in 2H) to match the vehicle’s road speed. This places a significant thermal and mechanical load on the transfer case synchronizer or clutch.

Technical documentation and owner’s manuals across the Ford lineup establish a clear consensus on the upper limit for this operation. For the Ford F-150 and Ford Ranger, the manufacturer consistently cites a maximum shifting speed of 68 mph (approximately 110 km/h). This specific velocity is calculated based on the thermal capacity of the synchronization mechanism. Attempting to engage 4H at speeds above this threshold may result in a “Shift Delayed” message on the instrument cluster, as the system protects itself from engaging when the speed differential is too great to bridge safely, or it may result in audible grinding as the locking collar attempts to mesh with a gear moving at a disparate speed.

For the Ford Super Duty, the parameters can be slightly more variable depending on the specific hubs (manual vs. auto) and transfer case, but the general guidance remains consistent with highway speeds. The Ford Bronco, particularly with its advanced electromechanical transfer case, is often cited as having Shift-on-the-Fly capability at “any speed,” though prudence dictates that shifting at speeds above 60 mph places unnecessary stress on the components.

Maximum Sustained Operating Speed

Once the 4H indicator is solidly illuminated on the dashboard, the synchronization phase is complete, and the front and rear drivelines are locked in unison. At this stage, the manual’s restriction on shifting speed no longer applies to driving speed. The owner’s manuals for the F-150, Bronco, and Super Duty generally do not list a specific maximum top speed for 4H operation.

This absence of a stated limit implies that the vehicle is mechanically capable of reaching its aerodynamic or electronic top speed while in 4H. Anecdotal evidence from the enthusiast community supports this. Owners of high-performance Ford trucks, such as tuned EcoBoost F-150s, frequently utilize 4H for drag racing launches. In these scenarios, the vehicles accelerate from a standstill to over 100 mph in 4H to maximize traction and prevent rear wheel spin. These reports verify that the transfer case and front differential can withstand the immense torque and rotational speeds of 100+ mph operation without immediate failure.

However, this mechanical capability comes with a significant caveat regarding the Super Duty platform. Unlike the F-150 and Ranger, which utilize Independent Front Suspension (IFS) with CV axles, the F-250 and F-350 utilize a solid front axle with U-joints at the steering knuckles. Engaging 4H at speeds exceeding 75 mph on a solid-axle truck significantly increases the rotating mass of the front end. If the vehicle has any existing wear in the track bar, ball joints, or steering damper, the gyroscopic forces of the spinning front axles can exacerbate steering oscillation, potentially triggering the phenomenon known as “death wobble”. Thus, while the transfer case allows 90 mph, the chassis dynamics of a heavy-duty truck often discourage it.

The “Safe Speed” Consensus: The 55 MPH Guideline

Despite the lack of a mechanical governor, a pervasive recommendation appears throughout expert commentary and conservative interpretations of Ford’s guidelines: the 55 mph (88 km/h) threshold. This figure is not derived from the burst strength of the steel gears but from the logic of environmental safety.

The reasoning is the “Traction Paradox.” 4H is explicitly indicated for “consistently slippery or loose surfaces” such as deep snow, sand, or mud. If a road surface is treacherous enough to require the additional longitudinal traction of 4H to maintain forward momentum, it is inherently too slippery to support safe braking or cornering at speeds above 55 mph. Conversely, if road conditions allow for safe travel at 70 or 80 mph, the surface provides enough traction that 4H is not only unnecessary but mechanically damaging due to windup. Therefore, the “speed limit” of 4H is a self-regulating function of road conditions: if you can go fast, you shouldn’t be in 4H; if you need 4H, you shouldn’t be going fast.

The Physics of Driveline Windup: The Primary Constraint

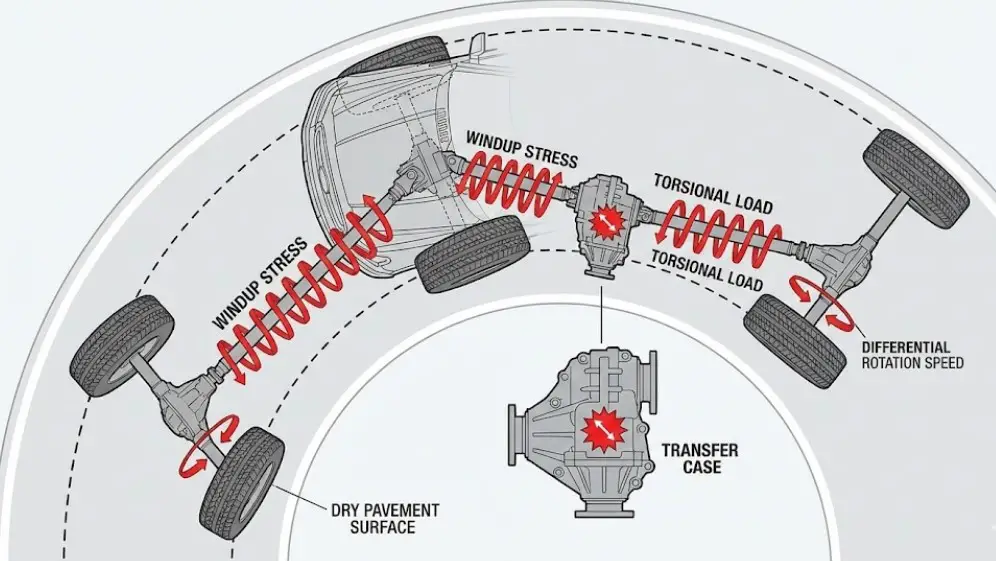

The most significant barrier to high-speed 4H operation is not the velocity of the vehicle, but the friction coefficient of the road surface. Ford’s documentation is unambiguous on this point, containing repeated warnings: “Do not use 4H or 4L mode on dry, hard surfaced roads”. To understand why speed exacerbates this restriction, we must explore the physics of driveline windup.

Ackerman Geometry and Path Differentiation

When a vehicle navigates a curve, the four wheels trace four distinct paths of varying lengths. According to Ackerman steering geometry, the inside front wheel must turn at a sharper angle than the outside front wheel. Furthermore, the rear wheels, which are fixed in their alignment, track inside the path of the front wheels. This results in the front axle traveling a significantly longer aggregate distance than the rear axle during any turning maneuver.

In a 2WD configuration, the front wheels are disconnected from the engine and rotate freely, allowing them to spin faster than the rear wheels to accommodate this longer path. In 4H, however, the transfer case locks the front and rear driveshafts together. This forces the front and rear axles to rotate at the exact same speed.

The Conflict of Traction

This mechanical lock creates a kinematic conflict. The geometry of the turn demands that the front wheels spin faster, but the transfer case forces them to spin at the same speed as the rear. This conflict must be resolved by one of two mechanisms:

- Tire Slip: On low-traction surfaces like snow, mud, or gravel, the tire contact patch breaks adhesion with the ground. The tire slips or skids microscopically, releasing the tension built up in the axle. This slip is the safety valve of the 4WD system.

- Driveline Windup: On high-traction surfaces like dry pavement or wet concrete, the tire grip is stronger than the torsional yield of the driveline components. The tires refuse to slip. Consequently, the energy that would normally be dissipated through slip is instead stored as potential energy (torque) within the axle shafts, the transfer case chain, and the driveshafts.

High-Speed Implications of Windup

While windup is most tactilely obvious during tight, low-speed parking maneuvers—where it manifests as “crow hopping,” shuddering, or binding steering—it is arguably more insidious at high speeds.

At highway speeds of 70 mph, the wheels are rotating approximately 800 to 1,000 times per minute. Even on a road that appears straight, highway driving involves constant micro-corrections, lane changes, and sweeping curves. Each of these deviations creates a path length difference between the axles. On dry pavement, this windup accumulates rapidly. At high rotational speeds, this torsional stress generates immense heat within the transfer case as the chain fights against the gears. This can lead to the vaporization of the oil film protecting the chain pins, causing rapid stretching of the chain.

Furthermore, if the vehicle encounters a sudden change in traction while “wound up”—such as hitting a patch of ice or a pothole—the stored energy can release violently, shock-loading the U-joints or CV axles and leading to catastrophic fracture. Thus, driving at 75 mph in 4H on dry pavement is a game of mechanical Russian Roulette, where the bullet is the accumulated torsional load waiting for a release point.

Vehicle-Specific Deep Dive: F-150, Super Duty, Bronco, and Ranger

While the fundamental physics of 4WD remain constant, the implementation varies across Ford’s portfolio. Each model presents unique considerations for high-speed 4H operation based on its specific engineering and intended use case.

Ford F-150: The High-Volume Standard

The F-150 utilizes a vacuum-actuated hub system known as Integrated Wheel Ends (IWE). In 2WD, the engine applies vacuum to the hubs to disengage them, holding a locking gear away from the wheel hub. In 4WD (or when the engine is off), the vacuum is cut, and a spring forces the gear to engage.

High-Speed Risk: A known failure mode in F-150s involves the check valve in the vacuum system. Under high engine load (such as accelerating to pass at highway speeds), engine vacuum drops (especially in EcoBoost models producing boost). If the check valve fails, the vacuum holding the hubs out may drop, causing the IWEs to partially engage while the wheels are spinning at 70 mph. This results in a destructive grinding noise. While this is a malfunction rather than a standard operation, frequent high-speed 4WD transitions can exacerbate wear on these vacuum components.

Drag Racing Context: As noted previously, the F-150 community has normalized the use of 4H for straight-line acceleration runs. In this specific context—straight line, high torque—the system is robust. The transfer case chain in the BorgWarner units used in the F-150 is exceptionally strong in tension. The risk in drag racing is not windup (since the path is straight) but rather the shock load of the launch.

Ford Super Duty (F-250/F-350): Heavy Mass Dynamics

The Super Duty is a distinct beast due to its solid front axle and sheer mass.

- Hub Operations: Super Duties feature manually selectable hubs with “AUTO” and “LOCK” positions. In “AUTO,” they function similarly to the F-150’s IWEs. However, at high highway speeds, the vacuum seal on the large knuckle can sometimes be compromised, leading to unreliable engagement.

- Towing Stability: A unique use case for the Super Duty is towing heavy loads in winter conditions. Owners frequently report using 4H at speeds of 60-65 mph to maintain directional stability while towing 10,000+ lbs trailers on snowy highways. The immense weight of the truck and trailer often ensures that the tires can force a slip on snowy surfaces, preventing windup. However, the manual strictly advises slowing down. The risk here is that if the trailer begins to sway or the truck hydroplanes, the rigid coupling of 4H can make recovery more complex.

Ford Bronco: G.O.A.T. Modes and High-Speed Desert Running

The 2021+ Ford Bronco was engineered with high-speed off-road driving as a core competency, particularly in the Raptor and Wildtrak trims.

- Baja Mode: This G.O.A.T. mode explicitly configures the vehicle for high-speed desert running. It engages 4H, relaxes the traction control intervention thresholds, and sharpens throttle response. In this environment, driving at 80+ mph in 4H is not only permitted but encouraged. The loose nature of sand provides zero resistance to driveline windup, and the suspension is tuned to handle the impacts.

- Short Wheelbase Dynamics: Conversely, on the 2-door Bronco, high-speed 4H usage on slick roads (ice/snow) requires extreme caution. The short wheelbase makes the vehicle more susceptible to yaw (spinning). If the rear axle breaks traction in 4H, the rigid connection can sometimes snap the vehicle into a spin faster than a 2WD vehicle with stability control active.

Ford Ranger: The Mid-Size Alternative

The Ranger shares much of its driveline DNA with the global Ford Everest. Its manual explicitly notes the ability to shift from 2H to 4H up to 68 mph.

- Thermal Protection: Advanced versions of the Ranger (such as the Ranger Raptor) utilize sophisticated thermal monitoring for the transfer case. In 4A mode, the system can actually reduce clutch pressure if it detects overheating. However, in the locked 4H mode, the system relies on the driver to adhere to surface guidelines. The lighter weight of the Ranger compared to the F-150 means it may be more prone to “skipping” or hopping during windup events on pavement, providing an earlier warning to the driver.

Environmental Analysis: Defining “Safe Speed” by Surface

Since mechanical limits are secondary to environmental ones, the “safe speed” for 4H operation is entirely dependent on the specific weather event the driver is navigating.

Snow and Ice: The Primary Use Case

Ideal Usage: 4H is the primary mode for roads fully covered in packed snow or ice.

Safe Speed Profile: If the road is covered in snow, the friction coefficient is significantly reduced. This allows for safe 4H operation without windup. However, the reduced friction also decimates braking performance.

- The Consensus Limit: Experts and safety guides suggest a maximum speed of 40–50 mph on snowy roads.

- The Patchy Road Danger: A common scenario is a highway that is mostly plowed but has patches of snow. Drivers often leave the truck in 4H and drive at 65 mph. This is highly damaging. On the clear patches, the driveline winds up. When the truck hits a snow patch, the built-up tension releases, potentially causing a momentary loss of traction or a “shock” to the wheels. For these conditions, 4A is the only mechanically sympathetic choice.

Rain and Wet Pavement: The Forbidden Zone

Ideal Usage: Do NOT use 4H.

Analysis: Rain reduces the friction coefficient of asphalt, but not enough to allow the continuous tire slip required to relieve 4WD windup. Driving in 4H on wet pavement at highway speeds will cause binding, steering fight, and accelerated tire wear.

- Hydroplaning Myth: A dangerous myth suggests that 4H prevents hydroplaning. This is false. Hydroplaning is a function of water depth, tire tread design, and vehicle speed. A vehicle in 4H will hydroplane just as readily as one in 2WD. When hydroplaning occurs, the tire rides on a layer of water, losing all contact with the road. Whether that tire is being driven by the engine or not is irrelevant to its lack of lateral grip. In fact, recovering from a hydroplane event in 4H can be more difficult because the front and rear axles are locked together, preventing the differential wheel speeds that might help stabilize the vehicle during a yaw event.

Sand and Mud: Momentum is King

Ideal Usage: 4H (or 4L for deep mire).

Safe Speed Profile: In deep sand, momentum is critical to prevent sinking. High wheel speeds are necessary to float the vehicle.

- The 50+ MPH Zone: It is common and safe to drive at 50 mph or more in 4H on beaches or desert washes. The shifting sand provides ample slip, ensuring no driveline stress accumulates. In these conditions, the engine’s power and the cooling system’s capacity are the only real limits.

The Safety Paradox: Braking and Stability

Perhaps the most critical aspect of the “how fast” question is the misconception regarding safety. Many drivers assume that because 4H allows them to accelerate to 60 mph on snow, it is safe to drive at 60 mph.

The Acceleration vs. Braking Disparity

4WD improves longitudinal acceleration traction. By distributing torque to four wheels instead of two, the vehicle can apply twice the power to the ground without spinning the tires. This masks the true slippery nature of the road. A driver in a 2WD truck might spin wheels at 20 mph, realizing the road is icy. A driver in a 4H F-150 might accelerate seamlessly to 50 mph, unaware of the low friction.

Stopping Distance: 4H does not decrease stopping distance. When the brakes are applied, the 4WD system is largely passive. Braking performance is dictated solely by the tires and the ABS system.

- Data from Consumer Reports: Testing consistently demonstrates that an AWD/4WD vehicle with all-season tires takes significantly longer to stop on snow than a 2WD vehicle with dedicated winter tires. The added mass of the 4WD components (transfer case, front axle) actually adds kinetic energy that the brakes must dissipate, potentially lengthening stopping distances compared to a lighter 2WD counterpart.

Stability Control Interactions

Ford’s AdvanceTrac system is tuned to work in concert with 4WD. When in 4H, the system may relax the yaw control thresholds, assuming the driver is in an off-road environment where some sliding is desirable. At high highway speeds on snow, this relaxed intervention can be dangerous if the driver is not skilled in correcting oversteer. Consequently, driving fast in 4H removes some of the electronic safety nets designed to catch the vehicle during a loss of control.

Operational Costs: Fuel Economy and Maintenance

Beyond the immediate risks of crashing or breaking parts, operating in 4H at high speeds incurs significant efficiency and maintenance penalties.

Parasitic Loss and Fuel Economy

Engaging 4H couples the entire front drivetrain to the engine. This includes the transfer case chain, the front driveshaft, the front differential gears, and the axle half-shafts. Even if the road is straight and no windup occurs, the engine must expend energy to spin this additional mass and overcome the friction of the cold gear oil in the front differential.

- Real-World Impact: User data and independent testing suggest a fuel economy penalty of 1–2 MPG when operating in 4H compared to 2H. This equates to a significant reduction in range over a long trip.

- 4A Efficiency: Interestingly, in 4A mode, the transfer case clutch is often kept at a low duty cycle or disengaged during steady-state cruising, which can offer slightly better fuel economy than locked 4H, though the hubs often remain engaged to allow for instant reaction, still incurring some drag.

Accelerated Wear

Continuous high-speed operation in 4H accelerates wear on several components:

- Transfer Case Chain: The chain stretches over time due to the constant tension, eventually becoming loose enough to slap the housing.

- Front Differential Fluid: In many trucks, the front differential holds less fluid than the rear and receives less airflow. Sustained high-speed driving heats this fluid, potentially degrading its lubrication properties faster than normal service intervals anticipate.

- IWE/Hubs: As mentioned, vacuum seals and diaphragms are stressed by the constant engagement and disengagement cycles if the driver frequently shifts on the fly at the 68 mph limit.

Summary of Operational Guidelines

Based on the exhaustive analysis of Ford’s engineering specifications, owner’s manual warnings, and physical laws, the following operational matrix establishes the definitive guidelines for 4H usage.

Table 1: Ford 4-High Operational Speed Matrix

| Drive Mode | Ideal Surface Condition | Max Shift-Into Speed | Max Operating Speed (Mechanical) | Recommended Safe Speed (Practical) | Dry Pavement Permitted? |

| 2H (2-High) | Dry Asphalt, Highway, Rain | N/A | Vehicle Top Speed | Posted Limit | YES |

| 4A (4-Auto) | Rain, Patchy Snow, Variable | Any Speed | Vehicle Top Speed | Posted Limit | YES |

| 4H (4-High) | Deep Snow, Sand, Mud | 68 mph (110 km/h) | Vehicle Top Speed* | < 55 mph (88 km/h) | NO |

| 4L (4-Low) | Rock Crawling, Recovery | < 3 mph (Neutral) | ~30-40 mph (RPM Limited) | < 15 mph | NO |

Conclusion

The definitive answer to “how fast can you go in 4 High” in a Ford vehicle is a nuanced duality between mechanical potential and environmental reality. Mechanically, the transfer cases and driveshafts in the F-150, Bronco, Ranger, and Super Duty are engineered to withstand rotational speeds equivalent to highway travel, with “shift-on-the-fly” protocols explicitly permitting engagement up to 68 mph. In specialized environments like desert racing, these systems successfully transmit torque at speeds exceeding 100 mph.

However, the operational limit is rigorously dictated by the road surface. 4 High is a mode designed exclusively for surfaces that permit tire slip. If a surface is slippery enough to necessitate 4H, it is universally unsafe to operate the vehicle at high highway speeds due to the severe degradation of braking performance and lateral stability. Conversely, if a road surface allows for safe travel at 75 mph, it provides too much traction for 4H, and engaging the system will inevitably result in driveline windup, causing accelerated wear and potential catastrophic failure of the transfer case or axle components.

Therefore, for the longevity of the vehicle and the safety of its occupants, Ford drivers should adhere to a simple heuristic: If the pavement is visible, remain in 2H. Utilize 4A (if equipped) as a high-speed safety net for variable conditions such as rain or patchy ice. Reserve 4H strictly for consistently loose or covered terrain—snow, mud, or sand—where speeds naturally and safely fall below 55 mph.