The Definitive Technical Report on the Ford 9-Inch Axle: Width Charts, Identification, and Engineering Specifications

In the pantheon of automotive engineering, few components have achieved the mythical status of the Ford 9-inch rear axle. Introduced in 1957 to replace the earlier banjo-style axles and the Dana units used in varying capacities, the 9-inch was designed not merely as a component for passenger transport but as a robust solution capable of handling the rapidly increasing horsepower figures of the late 1950s and the muscle car era that followed.

Its production run, spanning from 1957 through 1986, makes it one of the longest-serving drivetrain components in automotive history, finding a home in everything from the modest Ford Falcon to the heavy-duty F-150 and the legendary Shelby Mustangs.

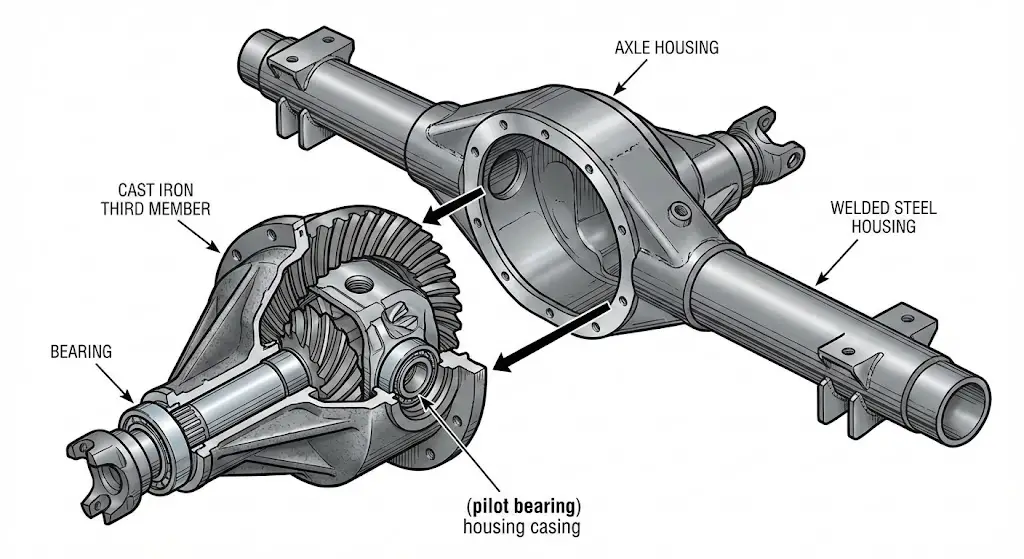

The enduring popularity of the Ford 9-inch among drag racers, off-road enthusiasts, and restorers is not an accident of history but a direct result of its superior architectural design. Unlike the Salisbury-style axles found in General Motors and Chrysler products—where the differential carrier is mounted directly inside the housing and accessed via a rear inspection cover—the Ford 9-inch utilizes a “dropout” carrier design. This “third member” or “hog’s head” bolts to the front of the axle housing.

This architecture offers two profound advantages that have solidified its dominance in motorsport: structural rigidity and serviceability. By eliminating the rear cover, the axle housing itself becomes a seamless, welded structural unit, significantly reducing tube deflection under high-torque launch conditions. Furthermore, the ability to remove the entire center section allows mechanics to swap gear ratios in a matter of minutes rather than hours, a critical capability in competitive racing environments.

However, the true genius of the 9-inch lies in its pinion support. In standard differentials, the pinion gear is supported by two bearings at the tail shaft. Under extreme load, the pinion gear can deflect away from the ring gear, leading to catastrophic gear tooth failure. The Ford 9-inch incorporates a third “pilot” bearing at the nose of the pinion gear, captured securely within the case. This tri-bearing support system maintains precise gear mesh alignment even under the immense torque loads generated by modern pro-mod drag cars or rock-crawling off-road rigs.

Despite its ubiquity, the “9-inch” is not a monolithic entity. It is a family of components that evolved over three decades. There are dozens of housing widths, multiple bearing sizes, varying axle spline counts, and distinct housing end patterns. A housing pulled from a 1966 Bronco will not fit a 1972 Torino, nor will the axles from a 28-spline Mustang carrier fit a 31-spline truck unit. This report aims to serve as the definitive technical compendium for these variations, aggregating granular data regarding dimensions, identification, and interchangeability to serve as the single source of truth for identifying, sourcing, and modifying Ford 9-inch axles.

Ford 9-Inch Guide

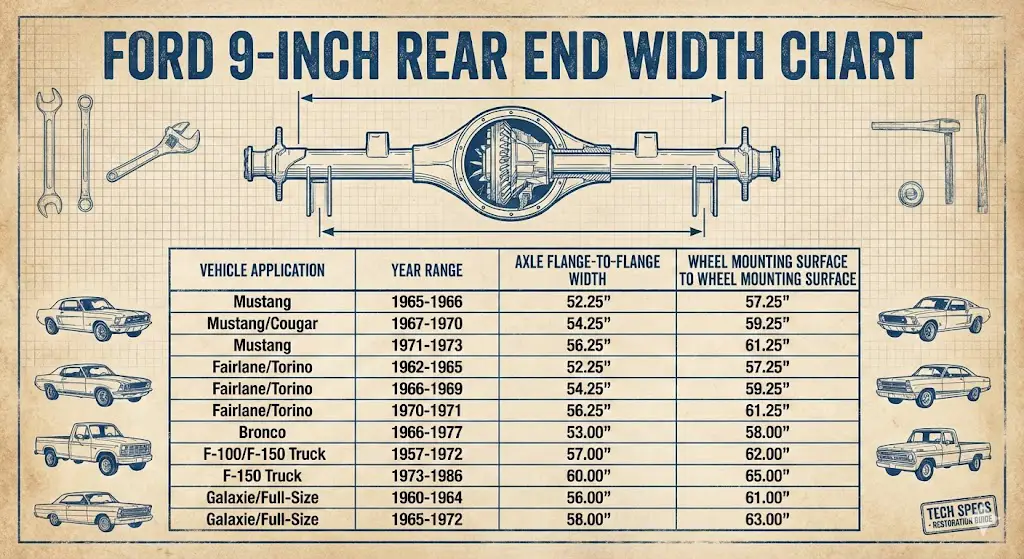

The Definitive Axle Width & Swap Chart

Why Width Matters

The Ford 9-inch rear end is the holy grail of drivetrains. It’s strong, easy to service, and found in millions of vehicles. However, not all 9-inch axles are created equal. The most critical factor for a swap is the width—specifically, the measurement from wheel flange to wheel flange. Get this wrong, and your tires will rub, or your wheels won’t fit. This guide breaks down the essential numbers you need for your project.

Popular Swap Widths

Comparison of “Flange-to-Flange” widths for the most sought-after donor vehicles. The 1957-1959 Ford and early Mustangs are prized for their narrow profiles, making them perfect for hot rods and compact swaps.

- Shortest: ’57-’59 Ford (57.25″)

- Mid-Range: ’67-’70 Mustang (59.25″)

- Widest: F-Series Trucks (65″+)

How To Measure Correctly

Accuracy is everything. Do not measure from the brake drums. You must measure from the Axle Flange (where the wheel bolts on) to the opposite Axle Flange.

The Golden Rule:

“Flange-to-Flange” is the standard. If measuring the housing only (no axles), add approximately 5 inches to get the total width (2.5″ per side for axle offset).

Master Width Chart

Common vehicles and their flange-to-flange measurements.

- 1965-1966 Mustang 57.25″

- 1967-1970 Mustang 59.25″

- 1971-1973 Mustang 61.25″

- 1967-1970 Cougar 59.25″

- 1966-1977 Bronco 58.00″

- 1957-1972 F-100 61.25″

- 1973-1979 F-100 65.25″

- 1978-1982 Bronco 65.25″

- 1957-1959 Ford 57.25″

- 1960-1964 Ford 61.25″

- 1958-1960 T-Bird 57.25″

- 1972-1979 Ranchero 61.25″

Spline Counts: What to Expect

The number of splines on the axle shaft dictates strength. 28-spline is common but weaker. 31-spline is the heavy-duty standard found in trucks and performance cars.

Is it a Real 9-Inch?

Don’t get fooled by the Ford 8-inch or 8.8. Here is how to spot the real deal in a scrapyard.

No Inspection Cover

The back of the housing is completely smooth and round. The bolts are on the front.

Removable “Third Member”

The entire center section (carrier) unbolts from the front of the axle housing.

Socket Access

The bottom two nuts retaining the carrier require a socket extension to reach (unlike the 8-inch, where you can use a wrench).

© 2026 FordMasterX Infographics. Data sourced from manufacturer owner manuals.

Housing Width Master Charts: The Critical Dimensions

The most frequently requested data regarding the Ford 9-inch is the physical width of the housing. This dimension dictates whether an axle will physically fit under a vehicle's fenders and whether the wheels will track correctly. It is paramount to distinguish between the two primary methods of measurement used in the industry, as confusing them can lead to costly fabrication errors.

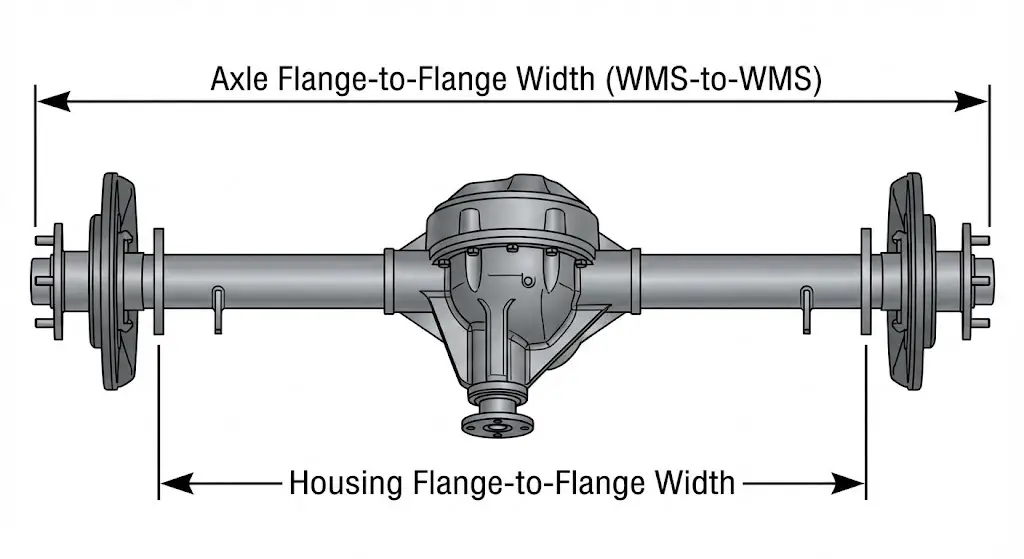

1. Housing Flange-to-Flange Width: This is the measurement of the bare steel housing, taken from the flat mounting face of one tube end to the flat mounting face of the other. This measurement does not include the axle shafts or brake hardware.

2. Axle Flange-to-Flange Width (Wheel Mounting Surface): Also known as "Wheel Mounting Surface to Wheel Mounting Surface" (WMS-to-WMS). This measures the total width from the face of the driver's side axle hub (where the wheel bolts on) to the face of the passenger's side axle hub.

- Fabrication Insight: As a general engineering rule for the Ford 9-inch, the Axle Flange Width is typically 5.00 inches wider than the Housing Flange Width. This accounts for the standard brake offset of approximately 2.50 inches per side.3

Passenger Car Housing Widths

The following data represents a synthesis of factory specifications and verified enthusiast measurements for Ford passenger cars. Note the trend of widening axles as vehicle generations evolved to accommodate wider tires and larger vehicle tracks.

| Vehicle Application | Production Years | Housing Width (Flange-to-Flange) | Axle Width (WMS-to-WMS) | Engineering Notes |

| Ford Mustang | 1965–1966 | 52.25" | 57.25" | The narrowest Mustang housing. Highly desirable for "tucked" wheel fitment on later cars. |

| Ford Mustang | 1967–1970 | 54.25" | 59.25" | Widened by 2 inches to accommodate the 390/428 big-block engine options and wider suspension geometry. |

| Ford Mustang | 1971–1973 | 56.25" | 61.25" | The widest classic Mustang housing, reflecting the larger "flatback" body style. |

| Ford Fairlane | 1962–1965 | 52.25" | 57.25" | Mechanically similar to the early Mustang; often interchangeable. |

| Ford Fairlane | 1966–1967 | 54.25" | 59.25" | Interchangeable with '67-'70 Mustang, though spring perch welds may vary slightly. |

| Ford Fairlane | 1968–1969 | 54.25" | 59.25" | Coil spring pockets may differ on certain models; verify suspension type. |

| Ford Torino | 1968–1969 | 54.25" | 59.25" | Shared platform with Fairlane. |

| Ford Torino | 1970–1971 | 56.25" | 61.25" | Widened track for improved stability. |

| Ford Torino | 1972–1973 | 56.25" | 61.25" | The "Big Car" intermediate width; distinct from the '72 truck width. |

| Ford Falcon | 1960–1965 | 52.00" | 58.00" | Extremely narrow. Early models often used the smaller 8-inch axle; verify the "socket test". |

| Ford Cougar | 1967–1970 | 54.25" | 59.25" | Mechanically identical to the 1967-1970 Mustang. |

| Ford Cougar | 1971–1973 | 56.25" | 61.25" | Follows the Mustang platform growth. |

| Lincoln Versailles | 1977–1980 | 53.50" | 58.50" | A legendary swap candidate due to factory disc brakes, though parts availability is now a challenge. |

| Ford Maverick | 1970–1977 | 51.50" | 56.50" | While mostly equipped with 8-inch axles, rare 9-inch performance options exist. |

| Ford Granada | 1975–1980 | 53.00" | 58.00" | An excellent, often overlooked donor for early Mustang swaps due to similar width. |

| Ford Galaxie | 1957–1959 | 52.25" | 57.25" | The narrowest heavy-duty 9-inch housing; highly prized for hot rod builds needing strength in a narrow package. |

| Ford Galaxie | 1960–1964 | 56.00" | 61.00" | Widened significantly for the full-size platform. |

Truck and Van Housing Widths

Truck housings differ not only in width but often in construction. They frequently utilize heavier-duty tubes, often measuring 3.25 inches in diameter compared to the standard 3.00-inch diameter found on passenger cars. This increased diameter provides greater resistance to bending loads during hauling or off-roading.

| Vehicle Application | Production Years | Axle Width (WMS-to-WMS) | Engineering Notes |

| Ford Bronco (Early) | 1966–1977 | 58.00" | The "Holy Grail" for narrow off-road swaps. Features the 5x5.5" bolt pattern. Note the 1976-77 models have wider brakes. |

| Ford Bronco (Full Size) | 1978–1986 | 65.00" | Significantly wider, based on the F-150 truck chassis. Too wide for most classic car swaps without narrowing. |

| Ford F-100 | 1957–1967 | 61.25" | A common width for early trucks; often 28-spline axles. |

| Ford F-100 | 1968–1972 | 61.25" | 31-spline axles become more common in this era. |

| Ford F-100/F-150 | 1973–1979 | 65.25" | The "Dent Side" era introduced a wider track width for stability; widely available in junkyards. |

| Ford F-150 | 1980–1986 | 65.25" | The final years of 9-inch production before the switch to the 8.8" axle. |

| Ford E-100 Van | 1968–1974 | 68.00" | Extremely wide. Primarily useful as a donor for the center section or for custom narrowing projects. |

| Ford E-200 Van | 1969–1974 | 69.25" | Maximum width; heavy-duty tubes often used. |

Strategic Fabrication Insight: The 1957-1959 Ford Ranchero and Station Wagon housings are uniquely valuable in the fabrication community. At 57.25 inches wide, they represent the narrowest factory 9-inch housings available that feature the strongest center sections and large-bearing housing ends. This makes them the ideal candidate for "tubbed" hot rods or early unibody swaps where wheel well clearance is at a premium, eliminating the need for expensive custom housing shortening services.

Spring Perch Locations and Suspension Geometry

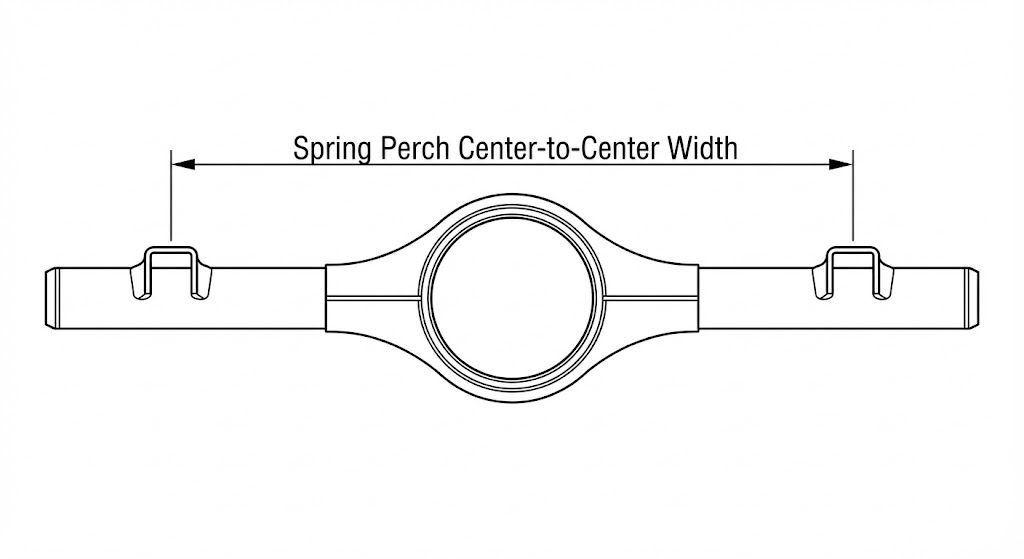

While the total width of the axle determines whether the tires will clear the fenders, the spring perch width determines whether the axle can be bolted to the vehicle's suspension. This is a critical distinction that often trips up novice builders. A housing might be the correct width for the wheels, but if the spring perches are 2 inches too wide, they will not align with the leaf springs, necessitating cutting and re-welding.

Welding on an axle tube requires care. Excessive heat can warp the tube, causing the axle bearings to misalign, leading to rapid bearing failure or vibration. It is recommended to weld perches in short stitches, allowing cooling time between passes.

Leaf Spring Perch Widths (Center-to-Center)

The following table details the center-to-center distance between the leaf spring mounting pads.

| Application | Perch Spacing (Center-to-Center) | Fabrication Notes |

| 1965–1973 Mustang | 43.00" | Remarkably consistent across all classic generations, making swaps between years straightforward regarding suspension mounting. |

| 1967–1970 Cougar | 43.00" | Identical to the Mustang platform. |

| 1960–1965 Falcon | 43.00" | Shares the compact Ford geometry. |

| 1966–1977 Bronco | 36.00" | Extremely narrow frame rails tailored for trail maneuverability. This narrow spacing is unique. |

| 1957–1959 Ford Car | 43.00" | Matches the Mustang spacing, reinforcing the value of these housings for Mustang swaps. |

| 1966–1967 Fairlane | 43.00" | Compatible with Mustang perches. |

| 1968–1969 Torino | 43.00" | Note: Some conflict exists in historical data for 1969 models; always verify before purchasing. |

| 1970–1971 Torino | 44.50" | The intermediate platform widened the spring spacing for stability. |

| 1972–1979 Ranchero | 44.50" | Matches the later Torino geometry. |

| Ford F-100 (Pre-73) | 34.00" | Very narrow frame rails on early trucks. |

| Ford F-100 (73-79) | 40.00" | The chassis redesign in 1973 significantly widened the rear frame rails. |

The Mustang vs. Bronco Discrepancy:

The difference between the Mustang (43 inches) and the Early Bronco (36 inches) perch widths is a common point of confusion. A 9-inch axle from an Early Bronco is often sought after for Mustang builds because it is narrow (58 inches wide), which allows for deep-dish wheels. However, the spring perches on a Bronco axle are 7 inches too narrow for a Mustang. To use a Bronco axle in a Mustang, the old perches must be cut off and new perches welded on at the 43-inch spacing. Conversely, putting a Mustang axle under a Bronco requires moving the perches inward.

Modern Truck Context:

While this report focuses on the legacy 9-inch, owners of modern Ford trucks (F-150s from 2004 onwards) often deal with different maintenance challenges, such as cam phaser issues on the Triton and Coyote engines. For those maintaining a mixed fleet of classic and modern Fords, understanding the evolution from the simple 9-inch to the complex modern drivetrains is key. For more on modern truck engine maintenance, referencing guides on Ford F-150 Cam Phaser Issues & Fixes can be beneficial for fleet managers.

Housing Ends and Bearing Identification: The "Big" vs. "Small" Dilemma

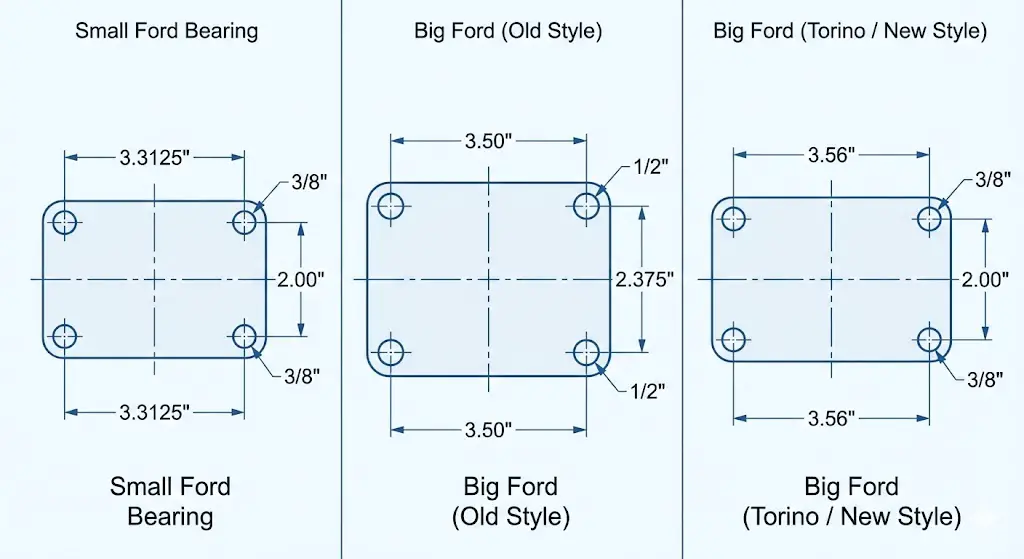

Identifying the "ends" of the axle housing—the flanges where the backing plates and brakes mount—is arguably more complex than determining the width. Ford utilized three primary flange patterns for the 9-inch, plus a specific variant for the Torino/Late model cars. The type of housing end determines the brake backing plate fitment, the bearing retainer mechanism, and the specific axle bearing required.

The "Big Bearing" vs. "Small Bearing" Classification

The terms "Big Bearing" and "Small Bearing" refer technically to the outer diameter of the ball bearing pressed onto the axle shaft, but in the field, they are identified by measuring the bolt pattern on the housing flange.

Small Bearing (Small Ford)

This is the standard end found on most light-duty passenger cars.

- Primary Applications: 1965-1973 Mustang, Cougar, Falcon, early Fairlane.

- Bolt Pattern: 3.3125" (3 5/16") horizontal x 2.00" vertical.

- Bolt Size: 3/8" diameter.10

- Bearing Specification: RW207 bearing (2.835" Outer Diameter).

- Brake Offset: 2.50 inches.

- Limitations: While adequate for street use, the smaller bearing surface area is less ideal for heavy side-loading found in autocross or hard cornering.

Big Bearing (Early Big Ford / Old Style)

Found on medium and heavy-duty vehicles, this end is significantly more robust.

- Primary Applications: Galaxie, F-100, Early Bronco, some big-block Fairlanes.

- Bolt Pattern: 3.50" horizontal x 2.375" (2 3/8") vertical.

- Bolt Size: 1/2" diameter.10

- Bearing Specification: 3.150" Outer Diameter.

- Brake Offset: 2.36 inches (Often rounded to 2 3/8" in conversation).

- Identification Tip: The use of large 1/2-inch bolts is the dead giveaway for the "Old Style" big bearing ends.

Big Bearing (Torino / Late Model / New Style)

This is the "modern" standard for the Ford 9-inch and is the most common end used in aftermarket housings today.

- Primary Applications: 1974+ Torino, Ranchero, Late Bronco, LTD.

- Bolt Pattern: 3.56" horizontal x 2.00" vertical.

- Bolt Size: 3/8" diameter.

- Bearing Specification: 3.150" Outer Diameter (Commonly uses the Set 20 Tapered Bearing).

- Brake Offset: 2.50 inches.

Why the "Torino" End Dominates the Aftermarket:

You might wonder why the "Torino" end has become the industry standard for companies like Currie and Strange Engineering. The answer lies in packaging. The Torino end combines the large 3.150" bearing capacity (for strength) with the standard 2.50" brake offset and, crucially, smaller 3/8" mounting hardware. The smaller bolt heads provide more clearance for caliper mounting brackets, making it easier to design compact disc brake kits.

Axle Shaft Bearings: Sealed Ball vs. Tapered Roller

The type of bearing used is not just a fitment issue; it dictates performance characteristics.

- Sealed Ball Bearing: Historically used in most passenger cars. It is a single unit containing the inner and outer race.

- Pros: Low friction, requires no adjustment, simple installation.

- Cons: Less effective at handling side-loading (lateral forces) experienced during hard cornering.

- Tapered Roller Bearing (Set 20): Standard in the Torino application and most aftermarket performance builds. These separate into a cup (pressed into housing) and cone (pressed on axle).

- Pros: Superior handling of side loads, making them preferred for circle track, autocross, and off-road applications.

- Cons: Requires an external seal to keep gear oil away from the brakes (unlike the sealed ball unit). Note that Set 20 bearings typically require a specific housing end designed for the seal.

Axle Shaft Specifications and Spline Counts

The ultimate torque capacity of a Ford 9-inch assembly is often limited by the axle shafts themselves. Ford produced them in two primary spline counts for factory vehicles, though the aftermarket has pushed this boundary significantly.

Factory Spline Counts: 28 vs. 31

The "spline count" refers to the number of teeth cut into the end of the axle shaft that engages with the differential side gears.

1. 28-Spline Axles:

- Usage: The vast majority of passenger cars (Mustang, Cougar, Fairlane) and light-duty trucks.

- Strength Rating: Generally accepted as safe for street tires and stock to mild horsepower (up to ~400-450 hp).

- Visual Identification: The face of the axle flange (the center hub) typically features a concave oval depression. If you see this oval, it is highly likely a 28-spline shaft.

- Failure Mode: Under hard launches with slick tires, 28-spline axles are prone to twisting at the splines or snapping cleanly.

2. 31-Spline Axles:

- Usage: High-performance applications (Boss 302/429, 427 Cobra Jet, Shelby GT500), F-150 trucks, Broncos, and Vans.

- Strength Rating: Significantly stronger due to increased diameter and tooth contact area; capable of handling 600+ hp in street/strip applications.

- Visual Identification: The face of the axle flange often features a countersunk center hole or two distinct dimples.

- Upgrade Path: Converting a 28-spline housing to 31-spline is the most common upgrade for street performance. It requires 31-spline axles and a matching 31-spline differential carrier (or spool). The housing tubes usually accommodate the slightly larger shaft diameter without modification.

Aftermarket Performance Options

For dedicated racing, the factory options are often insufficient.

- 35-Spline: Requires an aftermarket case with a larger bore size (3.250") and a spool or locker. This is the standard for serious drag racing (1000+ hp).

- 40-Spline: Reserved for Pro-Mod and Top Sportsman drag cars where launch forces are violent enough to shear lesser axles.

Measuring Axle Length Correctly

A common error in the garage is measuring axles incorrectly, leading to insufficient spline engagement or bottoming out.

- Measurement Standard: Measure from the outside face of the axle flange (wheel mounting surface) to the very end of the splines.

- The Pinion Offset Factor: The Ford 9-inch pinion is not centered in the housing; it is offset approximately 1 inch to the passenger side. Consequently, the housing tubes are different lengths, and the axle shafts are unequal lengths. The driver-side (left) axle is usually shorter than the passenger-side (right) axle.

- Example (Early Bronco): Left Axle = 27.125"; Right Axle = 29.625".

- Example (1965-66 Mustang): Left Axle = 26 1/8"; Right Axle = 30 1/8".

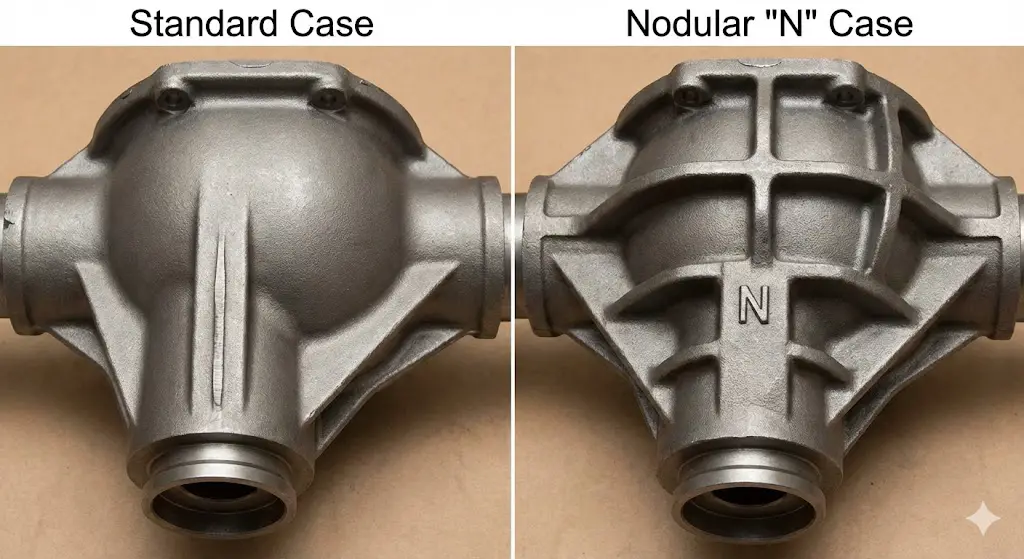

Third Member (Center Section) Identification and Metallurgy

The "Third Member," often called the "Pumpkin," "Chunk," or "Drop-out," contains the ring and pinion gears and the differential carrier. Identifying the case type is crucial for assessing the value and strength potential of a junkyard find.

Case Casting Identification: The "N" vs. "WAR"

The structural integrity of the third member is determined by the iron alloy and the reinforcing ribbing.

| Casting Mark | Type | Description | Strength Rating |

| No Mark (Plain) | Standard | Gray iron. Features a single vertical rib. The most common case found in passenger cars. | Stock / Mild Performance |

| WAR | Standard | Gray iron. Used in the mid-1960s. Generally considered the weakest design due to lower density iron. | Avoid for Performance Builds |

| WAB | Heavy Duty | Higher nodular content iron than standard. Features stronger webbing. | High Performance Street |

| N | Nodular | The "Holy Grail" of factory cases. Cast from high tensile nodular iron. Identified by a large "N" cast near the pinion pilot. | Race / High HP |

The "Two Dimple" Myth:

A pervasive myth in the community is that any center section with "two dimples" on the rear of the case is a 9-inch. This is false. Some Ford 8-inch rear ends also feature dimples.

- The Definitive Socket Test: To verify if a unit is a 9-inch or an 8-inch, attempt to place a standard socket and ratchet on the lower two nuts of the center section.

- If the socket fits over the nut and turns freely: It is an 8-inch axle.

- If the socket hits the casting and you must use a box-end wrench: It is a 9-inch axle. The 9-inch case is physically larger and shrouds the lower bolts.

The "Daytona" Pinion Support

High-performance 9-inch units (specifically the N-cases) often featured the "Daytona" pinion support.

- Standard Support: Uses a smaller inner pinion bearing. Adequate for stock power.

- Daytona Support: Uses a larger inner bearing and a stronger, thicker casting. This prevents the pinion gear from deflecting (bending) away from the ring gear under extreme torque loads. All aftermarket performance builds typically utilize a Daytona-style support as a baseline requirement.

Gear Ratio Codes and Tags

Ford offered a massive range of ratios, identified by a metal tag bolted to the carrier.

- Economy Gears: 2.75, 3.00 (Standard in non-GT Mustangs; aimed at fuel efficiency).

- Performance Gears: 3.25, 3.50 (The "sweet spot" for street performance).

- Drag/Towing Gears: 3.91, 4.11, 4.30 (Found in Drag Pack cars and heavy trucks).

- Decoding the Tag: A tag reading "3L50" indicates a 3.50 gear ratio with a Traction-Lok (Limited Slip) differential. The "L" stands for Locking. A tag reading simply "3.00" indicates an open differential.

Brake Systems and Swap Protocols

The braking system attached to the 9-inch is as varied as the housing itself. Upgrading from drums to discs is a common modification, but it requires navigating a minefield of offsets and bolt patterns.

Drum Brake Variations

- 10-inch Drums: Common on small-bearing, light-duty housings (early Mustang).

- 11-inch Drums: Found on big-bearing housings (Torino, Truck, Galaxie). These offer significantly more stopping power and heat dissipation but are heavy.

The Lincoln Versailles Disc Swap

For decades, the 1977-1980 Lincoln Versailles rear end was the go-to swap for 1965-1970 Mustangs.

- The Appeal: It is the correct width (58.5"), has factory disc brakes, and fits the Mustang spring spacing.

- The Drawbacks: The calipers are heavy iron units that are prone to seizing. Parts availability for these specific calipers is becoming scarce. The parking brake mechanism is notoriously complex and difficult to adjust.

- Modern Consensus: It is now often cheaper and more effective to buy a custom housing with "Torino" ends and install a modern Explorer-style or aftermarket disc brake kit than to rehabilitate a rusty Versailles axle.

The Explorer Disc Brake Swap

A popular modern junkyard upgrade involves adapting the disc brakes from a 1995-2001 Ford Explorer (8.8 axle) to a 9-inch housing.

- Compatibility: This requires a "Torino" style housing end.

- The Spacer Issue: The Explorer backing plate is thicker than a standard drum backing plate. To use Explorer brakes on a standard 9-inch axle shaft, a spacer ring is often required to fill the gap between the bearing and the retainer plate to ensure the bearing is preloaded correctly. Companies like Currie Enterprises produce specific spacer kits for this conversion.

Interchange and Swap Guide: What Fits What?

Swapping a 9-inch into a vehicle that didn't come with one (or upgrading to a stronger one) requires navigating the "what fits what" matrix.

The "Mustang" Swap (8.8 vs. 9-inch)

Owners of Fox Body (1979-1993) and New Edge Mustangs often debate swapping the factory 8.8" axle for a 9".

- The 8.8 Argument: The Ford 8.8 is lighter, consumes less parasitic power (more efficient gear mesh), and is cheaper. With C-clip eliminators and welded tubes, it handles significant power.

- The 9-Inch Argument: The 9-inch is virtually indestructible, easier to service (removable third member), and offers an infinite selection of gear ratios. However, it is heavier and has higher drivetrain loss.

- Recommendation: For street cars under 600hp, a built 8.8 is sufficient and efficient. For drag cars over 800hp, or off-road rigs turning 37"+ tires where shock loads are extreme, the 9-inch is mandatory.

Narrowing a Housing: The Process

If a direct-fit housing cannot be found (e.g., attempting to use an F-150 axle for a Mustang), the housing must be narrowed. This is a precision fabrication task.

- The Process:

- Cut off the existing housing ends.

- Calculate the new tube length:

(Total Desired Width) - (Axle Offset) - (Center Section Width). - Critical Step: Use a Solid Steel Alignment Bar. This is non-negotiable. The bar must run through the carrier bearing journals and out both tube ends. Pucks are used to center the bar in the new housing ends.

- Weld on the new ends (usually Torino style).

- Why the Bar Matters: Welding generates heat, which warps the tubes. Without the alignment bar holding the ends true during the cooling process, the ends will "toe in" or "toe out." This results in axle shafts that bind, destroying bearings in under 500 miles and causing severe vibration.

Lubrication and Maintenance: The API GL-6 Requirement

The Ford 9-inch has unique lubrication requirements due to its extreme hypoid offset.

The Hypoid Offset and Shear Forces

The 9-inch features a hypoid offset of 2.25 inches. This means the pinion gear contacts the ring gear exceptionally low. While this increases tooth contact area (strength), it creates a high-velocity sliding action between the teeth. This sliding creates extreme shear forces that can tear the oil film apart.

The GL-6 Standard

- The Requirement: To protect against this shear, Ford 9-inch axles require a gear oil with a very high concentration of Extreme Pressure (EP) additives. Historically, this was the API GL-6 specification. Although GL-6 is technically "obsolete" in the general market, specialty racing oil manufacturers (like Currie, Torco, and Motul) still formulate oils to meet this specific standard for 9-inch axles.

- The Synthetic Trap: Do not use standard off-the-shelf synthetic GL-5 oils in a high-performance 9-inch unless specified by the gear manufacturer. Many synthetics are too "slippery" for the specific sliding action of the 9-inch, preventing the protective phosphate coating on new gears from breaking in correctly. Furthermore, they may lack the specific sulfur/phosphorus buffer needed for the 2.25" offset.

- Recommendation: Use a high-quality mineral-based 85W-140 Racing Gear Oil rated for GL-6 applications.

Break-In Procedure

Failure to break in a new ring and pinion set is the #1 cause of gear whine and premature failure.

- Initial Drive: Drive 15-20 miles conservatively. Vary the speed, but do not exceed 60 MPH. Do not launch hard.

- Cool Down: Stop the vehicle and let the differential cool completely (30-60 minutes). This heat cycle hardens the work surfaces of the gear teeth.

- Repeat: Perform this cycle for the first 500 miles.

- Fluid Change: Change the fluid at 500 miles. You will find gray metal paste on the magnet; this is normal (it is the phosphate coating and minor machining peaks wearing off). If you see large chunks, you have a problem.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Even the legendary 9-inch is not immune to problems, most of which stem from improper setup.

Diagnosing Gear Whine

- Drive Side Whine: A howling noise under acceleration usually indicates improper backlash (too tight or too loose) or incorrect pinion depth.

- Coast Side Whine: Noise when letting off the gas suggests the pinion preload has loosened (check the pinion nut) or the contact pattern is too far toward the toe or heel of the tooth.

- Constant Whine: A noise that is present at all speeds, regardless of acceleration or deceleration, usually points to carrier bearings or pinion bearings that are pitted or worn.

- Aftermarket Gears: Be aware that "Pro Gears" or high-strength aftermarket gears (like Richmond) are often cut with a different tooth profile for maximum strength rather than silence. A slight whine may be inherent to these racing gears.

Leaks

- Pinion Seal: The most common leak point. Before replacing the seal, inspect the yoke. If the yoke sealing surface has a groove worn into it from the old seal, a new seal will not fix the leak. You must install a "speedi-sleeve" on the yoke or replace the yoke entirely.

- Third Member Gasket: Leaks between the housing and the third member are common. Use a high-quality reusable gasket or a specific RTV. Crucial Tip: Ensure the copper washers (or soft metal washers) are used under the nuts that secure the third member. These washers crush to seal the oil from seeping past the stud threads.

- Axle Seals: If oil is leaking onto the brakes, identify the bearing type.

- Sealed Bearing: The bearing itself has failed. Replace the bearing.

- Tapered Bearing: The outer seal (pressed into the housing end) has failed. Replace the seal and check the axle shaft surface for damage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Can I put 31-spline axles in a 28-spline housing?

Answer: Yes, generally. The housing tubes themselves are typically the same diameter. However, you must change the differential carrier (or side gears) to accept 31-splines. You cannot simply jam 31-spline axles into a 28-spline carrier. Also, verify that the housing ends (bearing size) match the new axles. If you have a small-bearing housing, you will need special "conversion bearings" to run 31-spline axles.

Q2: How do I tell if I have a "War" case or an "N" case?

Answer: Look at the casting ribs on the front of the third member. An "N" case has a large "N" stamped near the pinion pilot and features thick, reinforced webbing. A "WAR" case will have the letters "WAR" cast into it and is considered the weakest factory design. A standard case typically has a single vertical rib and no specific letter markings.

Q3: What is the exact width of a 1967 Mustang rear end?

Answer: The housing flange-to-flange width is 54.25 inches. The axle flange-to-flange (wheel mounting surface) width is 59.25 inches.

Q4: Will a Ford Explorer 8.8 rear end fit a vintage Mustang?

Answer: The Explorer 8.8 is approximately 59.5" wide, which fits 1967-1970 Mustangs well regarding track width. However, there are complications:

- The pinion is offset roughly 2 inches to the passenger side, which can cause driveshaft tunnel clearance issues in a lowered Mustang.

- The spring perches are in the wrong location and must be cut and moved to the Mustang spacing of 43 inches.

- The axle tubes are larger diameter (3.25"), requiring new U-bolts and shock plates.

Q5: What is the best oil for a Ford 9-inch?

Answer: A mineral-based 85W-140 racing gear oil that meets API GL-6 specifications is highly recommended to handle the high-offset sliding friction. Avoid off-the-shelf synthetic GL-5 oils unless they are specifically approved by your gear manufacturer (e.g., some Motul or Amsoil racing blends).

Q6: What is the difference between Torino ends and Big Ford Old Style ends?

Answer: Both utilize the large 3.150" bearing. However, the "Old Style" has a bolt pattern of 3.50" x 2.375" and uses 1/2-inch bolts. The "Torino" (New Style) has a pattern of 3.56" x 2.00" and uses 3/8-inch bolts. The Torino end is the standard for modern aftermarket disc brake conversions due to the clearance provided by the smaller bolt heads.

Conclusion

The Ford 9-inch rear end remains the preeminent choice for performance applications not by accident, but by design. Its removable center section, nose-supported pinion, and massive aftermarket ecosystem allow it to be adapted to virtually any vehicle, from a 1932 Ford Roadster to a 1000hp trophy truck. It is a piece of automotive history that continues to outperform modern designs in the harshest environments.

However, success with the 9-inch platform requires precision. "Close enough" measurements regarding housing width, bearing type, or pinion offset can lead to brake failure, axle misalignment, or differential destruction. By utilizing the width charts and identification protocols outlined in this report, builders can ensure they select the correct housing, axles, and components for their specific build, preserving the legend of the 9-inch for another generation of high-performance driving.