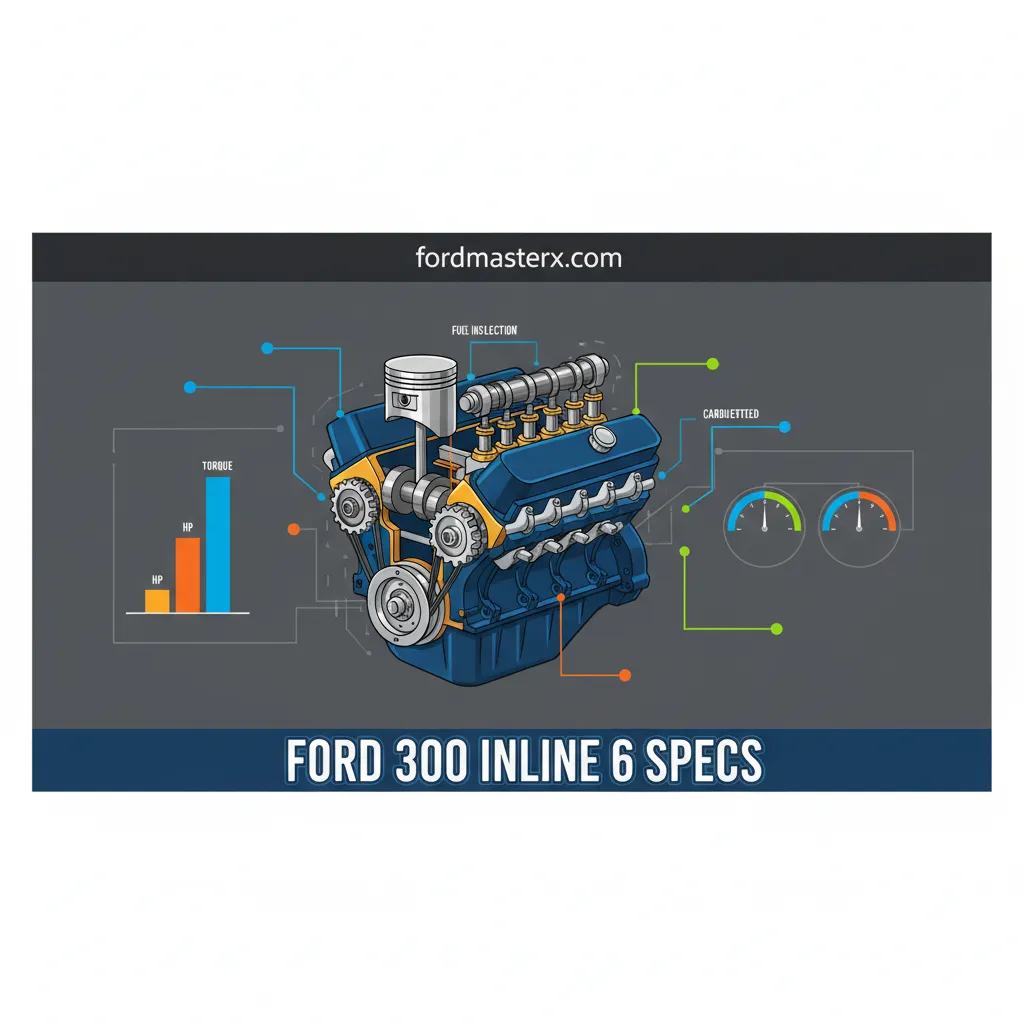

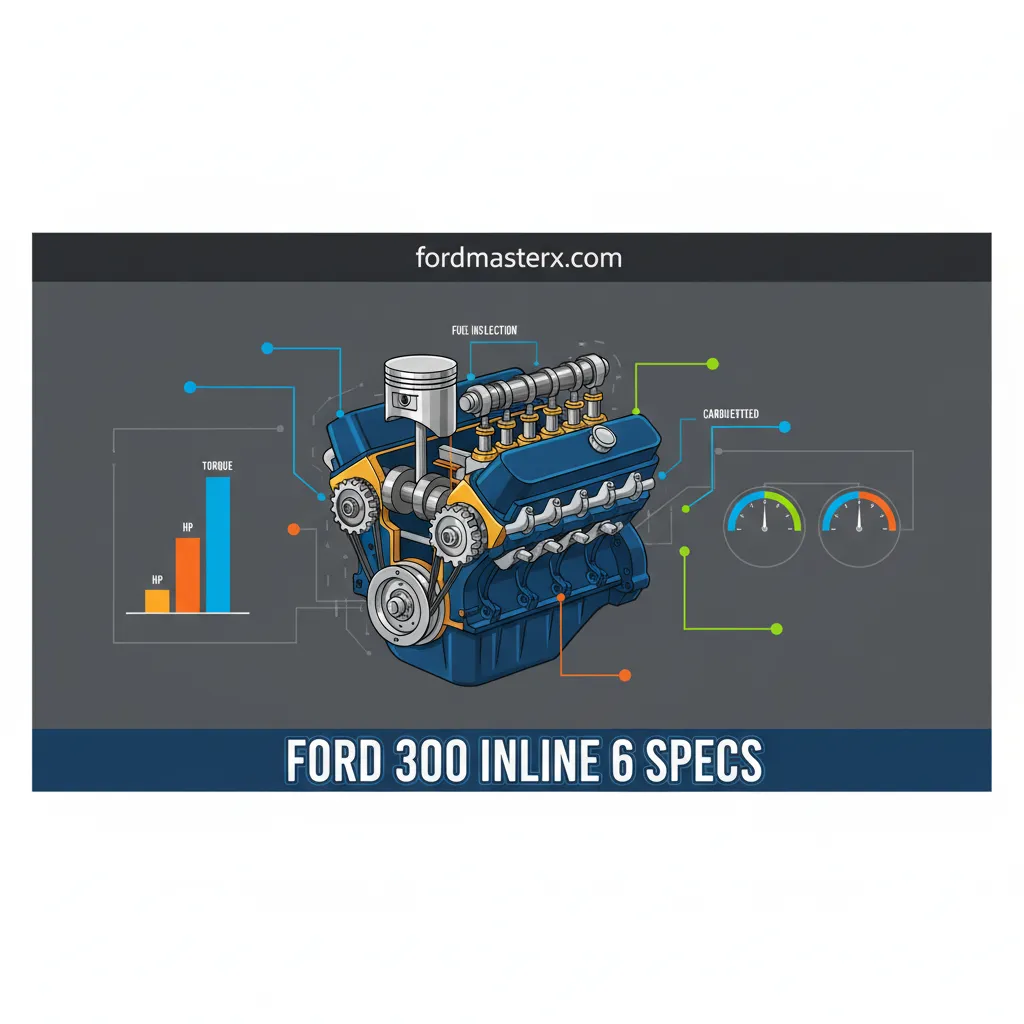

Ford 300 Inline 6 Specs: Technical Architecture And Performance Characteristics

Widely regarded as one of the most durable internal combustion engines ever produced, the Ford 300 cubic inch (4.9L) inline-six is a masterpiece of industrial utility. Originally introduced in 1965 as part of the fourth generation of Ford six-cylinder engines, it served as the backbone of the American work fleet for over three decades. While many enthusiasts appreciate its reputation for longevity, finding a consolidated technical breakdown of its specific engineering tolerances, output variations, and internal components can be difficult. This article provides a rigorous analysis of the Ford 300 inline 6 specs, covering everything from its high-torque architecture to its generational performance evolutions.

Section 1: Core Engine Architecture and Dimensional Ford 300 Inline 6 Specs

📤 Share Image

The Ford 300 (4.9L) is built upon a fundamental design philosophy that prioritizes structural rigidity and thermal stability over lightweight performance. At the heart of its technical architecture is a cast-iron engine block and cylinder head. Unlike modern engines that utilize aluminum alloys to shed weight, the heavy-wall iron casting of the 300 provides a stable platform that resists warping under the extreme heat cycles common in towing and industrial service.

Geometry and Displacement Dynamics

The engine features a 4.00-inch bore and a 3.98-inch stroke. This nearly square geometry is a critical specification that dictates the engine’s personality. While a 4.00-inch bore is identical to that of a Ford 302 V8, the 300’s significantly longer stroke allows for greater leverage on the crankshaft. This geometric configuration favors torque production at the low end of the power band rather than high-RPM horsepower. When compared to the contemporary Ford 302 V8, the 300 produces its peak torque almost 1,000 RPM earlier, making it a superior choice for heavy-load takeoffs.

The Seven Main Bearing Advantage

One of the most impressive technical aspects of the Ford 300 is its use of seven main bearings. In an inline-six configuration, having a main bearing between every crank throw significantly reduces crankshaft flex. This is a level of over-engineering typically reserved for diesel engines. By distributing internal loads across seven supports, the 300 minimizes vibration and bearing wear, contributing directly to its 300,000+ mile capability.

Fundamental Architecture Specs

Displacement (300 CID)

Main Bearings

Firing Order

Finally, the Ford 300 utilizes a gear-driven camshaft. By eliminating a timing chain or belt, Ford removed a common failure point found in almost every other overhead valve engine. The precision of direct gear-to-gear contact ensures that valve timing remains consistent even after decades of use, a feature that is legendary among fleet mechanics.

Section 2: Internal Component Engineering and Rotating Assembly Features

The internal performance characteristics of the 4.9L are defined by high-strength metallurgy. Depending on the intended application—light truck versus industrial/heavy-duty—Ford utilized different materials for the rotating assembly. While standard F-150s typically received a cast nodular iron crankshaft, heavy-duty and industrial versions (used in wood chippers, generators, and large trucks) often featured a forged steel crankshaft.

Rod Length and Piston Dwell Time

A critical detail often overlooked is the connecting rod length. The Ford 300 uses 6.21-inch rods, resulting in a rod/stroke ratio of 1.56. This relatively high ratio for a long-stroke engine increases “piston dwell time” at top dead center (TDC). In a practical scenario involving heavy towing, this increased dwell time allows for more complete combustion and a gradual pressure rise, which prevents the engine knock (detonation) that often plagues shorter-rod engines under high-load/low-RPM conditions.

Valvetrain and Piston Design

- OHV System: The pushrod-actuated overhead valve system is designed for simplicity. It uses hydraulic lifters and a rocker arm ratio that prioritizes reliability over high-lift air flow.

- Piston Profiles: Early carbureted models used relatively flat-top pistons, while later EFI models (1987–1996) utilized deep-dish crowns. These “D-cup” pistons were essential for managing compression ratios and optimizing flame propagation for emissions compliance.

- Thermal Management: The heavy-duty pistons often featured higher silicone content to manage thermal expansion during continuous wide-open-throttle operation in industrial settings.

If you are rebuilding for extreme performance or turbocharging, source a crankshaft from an industrial 300 (often found in wood chippers or airport tugs). The forged steel unit is significantly stronger than the standard nodular iron crank found in the F-150.

Section 3: Induction Systems and Fuel Delivery Functionality

The evolution of the Ford 300’s induction system is a case study in the transition from simple mechanical fuel delivery to sophisticated electronic control. For the first 22 years of its life, the engine relied on the Carter YF and YFA single-barrel carburetors. These units were prioritized for ease of maintenance and consistent fuel metering at low vacuum, though they were notorious for “stumbling” during extreme off-road inclines.

The 1987 EFI Revolution

In 1987, Ford introduced Electronic Fuel Injection (EFI), which fundamentally changed the engine’s capability. The EFI intake manifold is a “dual-runner” design that looks more like a set of headers than a traditional intake. This long-runner design increased air velocity into the cylinders, further enhancing the engine’s already impressive low-end torque. Additionally, the EFI cylinder heads featured high-swirl combustion chambers to improve quality of combustion and reduce emissions.

Port Geometry and Breathing

The intake valve diameter of 1.78 inches and exhaust valve of 1.56 inches are modest for a 4.9L engine. This was an intentional aspect of the design; small ports keep air velocity high. High velocity translates to excellent cylinder filling at low RPMs. For enthusiasts seeking more performance, a common function of modification is retrofitting an Offenhauser four-barrel intake manifold with a small 390-500 CFM carburetor, which “unwraps” the engine’s ability to breathe at higher RPMs without sacrificing low-end grunt.

Section 4: Output Capability and Generational Performance Detail

When analyzing Ford 300 inline 6 specs, one must distinguish between “Gross” and “Net” horsepower ratings. In the 1960s and early 70s, engines were rated without accessories like water pumps or alternators. By the 1990s, the measurements were much more realistic. However, the one constant across every era was the quality of its torque curve.

Torque: The Engine’s Primary Function

The Ford 300 is often called “the tractor engine” because it produces 90% of its peak torque at just 1,200 RPM. This is why it was the primary choice for UPS delivery trucks, airport tugs, and agricultural equipment. It doesn’t need to “rev up” to move a load; it simply applies brute force immediately from idle. In the final years of production (1996), the 4.9L EFI reached its peak refinement, producing 150 HP @ 3,400 RPM and 260 lb-ft of torque @ 2,000 RPM.

Utility-First Power

Peak torque arrives at 2,000 RPM, allowing heavy trucks to pull away from stops with ease.

Industrial Reliability

Low operating RPMs (seldom exceeding 3,000) result in drastically reduced internal component wear.

The Impact of Emissions Controls

The mid-1970s saw a dip in performance as Ford introduced smog pumps, Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR) valves, and restrictive catalytic converters. While these details reduced the peak output numbers on paper, the engine’s fundamental ability to move heavy loads remained largely unchanged. By the 1990s, the addition of the Thick Film Ignition (TFI) system and computerized fuel management restored the engine’s efficiency and cold-start reliability to modern standards.

Section 5: Maintenance Requirements and Operational Durability Characteristics

While the Ford 300 is famously “bulletproof,” its longevity is predicated on adhering to specific maintenance requirements. Because this is a flat-tappet camshaft engine, modern low-zinc oils can be problematic. Using a high-zinc additive or specialized high-mileage oil (such as a 10W-30 or 15W-40) is a critical step in protecting the cam lobes from premature wear.

Certain production years used “phenolic” (plastic-fiber) cam gears to reduce engine noise. These are the primary failure point of the 300. If your engine has over 150,000 miles, inspect these gears. Many builders proactively replace them with aluminum or steel gears for absolute reliability.

📋

Operational Maintenance Guide

Capacity is 6 quarts with a filter. Use 10W-30 and ensure an oil with ZDDP (Zinc) content to protect the flat-tappet valvetrain.

For EFI models, set the spark plug gap to 0.044 inches. Inspect the TFI module for heat damage and use thermal paste during replacement.

Ensure the #6 cylinder (rear of the block) receives adequate flow. Flush the system biennially to prevent localized hot spots that can lead to head cracking.

Million-Mile Potential

Anecdotal evidence from F-150 and Econoline owners often places the Ford 300 in the “Million Mile Club.” This is not hyperbole; the engine’s quality is such that, when maintained, the vehicle’s body and chassis will typically rot away long before the engine suffers a catastrophic mechanical failure. By prioritizing cooling system efficiency and high-quality lubricants, you can ensure this industrial powerhouse remains in service for decades to come.

The Ford 300’s overbuilt seven-main-bearing design is the foundation of its legendary reliability. Its torque-centric performance specifications made it the preferred choice for heavy-duty fleet operations for over three decades, outlasting and outperforming more complex V8 engines in utility tasks. Whether in carbureted or EFI form, the 4.9L remains a benchmark for low-end power and mechanical simplicity. For those restoring a vintage F-Series or maintaining a classic 4.9L, prioritize high-quality lubricants and cooling system maintenance to ensure another 300,000 miles of service. The Ford 300 is not just an engine; it is a monument to an era where durability was the primary engineering objective.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the Ford 300 an interference engine?

No, the Ford 300 inline-six is a non-interference design. This means that in the unlikely event of a timing gear failure, the pistons will not strike the valves. This characteristic adds a layer of safety for the engine internals, preventing catastrophic mechanical damage during a timing synchronization loss.

What is the difference between the Ford 240 and the 300 inline 6?

The Ford 240 and 300 share the same engine block architecture; however, the 300 features a longer stroke (3.98 inches vs. 3.18 inches). Additionally, the 240 has smaller combustion chambers in the cylinder head, which enthusiasts often swap onto 300 blocks to increase the compression ratio for performance gains.

Why is the Ford 300 referred to as the 4.9L?

In the mid-1980s, Ford transitioned to metric labeling for its engine lineup. While the displacement is technically 4.916 liters, Ford marketed it as the 4.9L to distinguish it from the 5.0L (302 CID) V8, despite the two engines having very different performance characteristics and intended use cases.

What are the most common performance upgrades for the Ford 300?

Common upgrades include replacing the restrictive factory exhaust manifold with EFI-style split manifolds or long-tube headers, installing a four-barrel carburetor with an aftermarket intake, and swapping the factory phenolic cam gear for a steel set to ensure permanent timing reliability under high-load conditions.

What is the maximum RPM for a stock Ford 300?

A stock Ford 300 is designed for low-to-mid-range operation. The factory redline is typically around 4,000 to 4,500 RPM, but peak power is usually achieved by 3,400 RPM. Revving beyond this point is generally counterproductive as the head’s port geometry cannot flow enough air to sustain power at higher frequencies.