The Ultimate Technical Analysis of Ford FE and FT Engine Specifications: Bore, Stroke, and Engineering Evolution

In the late 1950s, the American automotive landscape was undergoing a seismic shift. The horsepower wars were in their infancy, vehicles were growing in size and weight, and the existing powertrain technologies were rapidly reaching their architectural limits. For the Ford Motor Company, this reality necessitated a departure from the venerable Y-Block V8, which had served faithfully since 1954 but was constrained by its displacement ceiling of roughly 312 cubic inches.

The solution was a clean-sheet design that would come to define Ford performance for the next two decades: the FE (Ford-Edsel) engine family.

Introduced in 1958, the FE engine was not merely a larger engine; it was a modular platform designed with future expansion in mind. The architecture was engineered to power everything from the mid-priced Edsel lineup to the utilitarian F-Series trucks, and eventually, to dominate the global racing stage at Le Mans. The significance of the FE engine lies in its versatility.

Through a strategic manipulation of bore and stroke dimensions, Ford engineers were able to extract a staggering range of displacements—from the modest 332 cubic inch economy motor to the earth-shaking 428 Cobra Jet—all from the same basic external envelope.

This report provides an exhaustive technical analysis of the FE and its heavy-duty sibling, the FT (Ford Truck) series. Beyond a simple recitation of specifications, we will explore the engineering rationale behind the bore and stroke combinations, the metallurgical advancements in thin-wall casting that made the FE lighter than its competitors,

and the intricate interchangeability rules that challenge modern engine builders. By synthesizing factory data, casting analyses, and performance benchmarks, we aim to provide the most authoritative resource available on the subject.

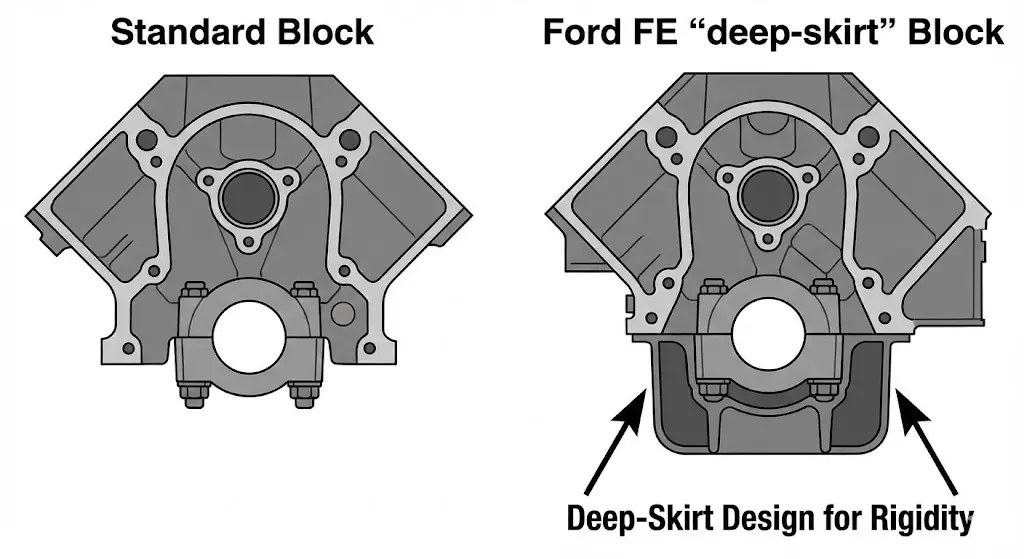

The Engineering Philosophy: Deep Skirts and Thin Walls

To understand the bore and stroke capabilities of the FE, one must first understand the block itself. The FE utilizes a “deep-skirt” block design, a feature inherited and refined from the Y-Block. In this configuration, the cylinder block casting extends well below the centerline of the crankshaft. This architectural decision provides immense structural rigidity, allowing the main bearing caps to be supported by a greater volume of iron. This rigidity is the primary reason why stock FE blocks, even two-bolt main versions, can withstand horsepower levels that would split the blocks of competitor engines.

Simultaneously, Ford employed advanced “thin-wall” casting techniques for the FE. By precisely controlling the mold cores and metal flow, engineers could reduce the thickness of non-structural walls, thereby reducing overall weight without compromising strength in critical areas. A fully dressed iron FE engine weighs approximately 650 lbs, which is remarkably competitive against the 700+ lb big blocks from General Motors and Chrysler of the same era. This weight advantage, combined with the block’s inherent strength, created the perfect foundation for the displacement increases that would follow.

Ford FE Engine Specifications

Bore, Stroke & Displacement Reference Guide

The Ford-Edsel (FE) engine family powered everything from the Thunderbird to Le Mans GT40s. Use this interactive infographic to decode the precise bore and stroke combinations that define these legendary powerplants.

Bore vs. Stroke Architecture

The defining characteristic of any V8 is its cylinder dimensions. The FE family is unique because of its massive interchangeability. Notice how the 390 and 427 share the same 3.78" stroke, but the 427 achieves its displacement through a massive 4.23" bore. Conversely, the 428 Cobra Jet utilizes a smaller bore but a longer 3.98" stroke for massive low-end torque.

Figure 1: Comparison of Cylinder Dimensions (Inches)

The Definitive FE Chart

Complete specifications list. Sort by displacement to identify your block.

| Engine (CID) | Bore (in) | Stroke (in) | Configuration | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 332 | 4.00 | 3.30 | Over-square | Early Edsel/Ford (1958-59) |

| 352 | 4.00 | 3.50 | Over-square | Standard Passenger Car |

| 360 | 4.05 | 3.50 | Over-square | F-Series Trucks (Workhorse) |

| 390 | 4.05 | 3.78 | Performance | Mustang, Galaxie, Thunderbird |

| 406 | 4.13 | 3.78 | Over-square | NASCAR Homologation |

| 410 | 4.05 | 3.98 | Under-square | Mercury Models Only |

| 427 | 4.23 | 3.78 | Racing | GT40, AC Cobra, Fairlane |

| 428 | 4.13 | 3.98 | Cobra Jet | Mustang, Shelby GT500 |

Figure 2: Bore/Stroke Ratio & Total Displacement

The "Squareness" Ratio

This scatter plot reveals the character of the engines. Engines higher on the Y-axis (Bore) breathe better at high RPMs (like the 427). Engines further right on the X-axis (Stroke) produce more torque but have lower redlines due to piston speed limits (like the 410/428).

- The 427: Huge bore (4.23") with moderate stroke (3.78") = High RPM Screamer.

- The 390: The balanced performer. Good bore/stroke ratio for both street and strip.

- The 360: Small bore, short stroke, but low compression. A low-stress truck engine.

Rod Ratio Dynamics

The Rod Ratio (Connecting Rod Length ÷ Stroke) dictates piston

side-loading. A higher ratio generally means less friction and

better high-RPM capability.

The 427 stands out again with a higher ratio,

emphasizing its racing heritage. The 428, with its

long stroke, has a lower ratio, prioritizing torque but increasing

cylinder wall stress at high RPM.

Figure 3: Rod Ratio (Higher is generally better for high RPM)

© 2026 FordMasterX Infographics. Data sourced from manufacturer owner manuals.

The Master Ford FE and FT Bore and Stroke Chart

The modular nature of the FE engine family allows for a complex matrix of displacements derived from a relatively small set of crankshafts and bore diameters. Understanding these relationships is critical for identification and performance planning. The FE family generally shares a common deck height of approximately 10.17 inches, allowing for interchangeable rotating assemblies, provided the block's cylinder walls can support the necessary bore.

Table 1: Complete Ford FE and FT Engine Dimensions

| Engine Family | Displacement (ci) | Bore (in) | Stroke (in) | Connecting Rod Length (in) | Production Years | Primary Application |

| FE | 332 | 4.000 | 3.300 | 6.540 | 1958–1959 | Ford/Edsel Passenger Cars |

| FE | 352 | 4.000 | 3.500 | 6.540 | 1958–1967 | Passenger Cars / F-Series |

| FE | 360 | 4.050 | 3.500 | 6.540 | 1968–1976 | F-Series Trucks |

| FE | 361 (Edsel) | 4.050 | 3.500 | 6.540 | 1958–1959 | Edsel Ranger / Pacer |

| FE | 390 | 4.050 | 3.784 | 6.490 | 1961–1976 | Galaxie / Mustang / T-Bird |

| FE | 406 | 4.130 | 3.784 | 6.490 | 1962–1963 | High Performance Racing |

| FE | 410 | 4.050 | 3.980 | 6.490 | 1966–1967 | Mercury Park Lane / Monterey |

| FE | 427 | 4.230 | 3.784 | 6.490 | 1963–1968 | NASCAR / Le Mans / Cobra |

| FE | 428 | 4.130 | 3.980 | 6.490 | 1966–1970 | Cobra Jet / Police Interceptor |

| FT | 330 MD | 3.875 | 3.500 | 6.540 | 1964–1978 | Medium Duty Trucks (F-600) |

| FT | 330 HD | 3.875 | 3.500 | 6.540 | 1964–1978 | Heavy Duty Trucks |

| FT | 361 | 4.050 | 3.500 | 6.540 | 1964–1978 | Heavy Duty Trucks |

| FT | 391 | 4.050 | 3.780 | 6.490 | 1964–1978 | Heavy Duty Trucks |

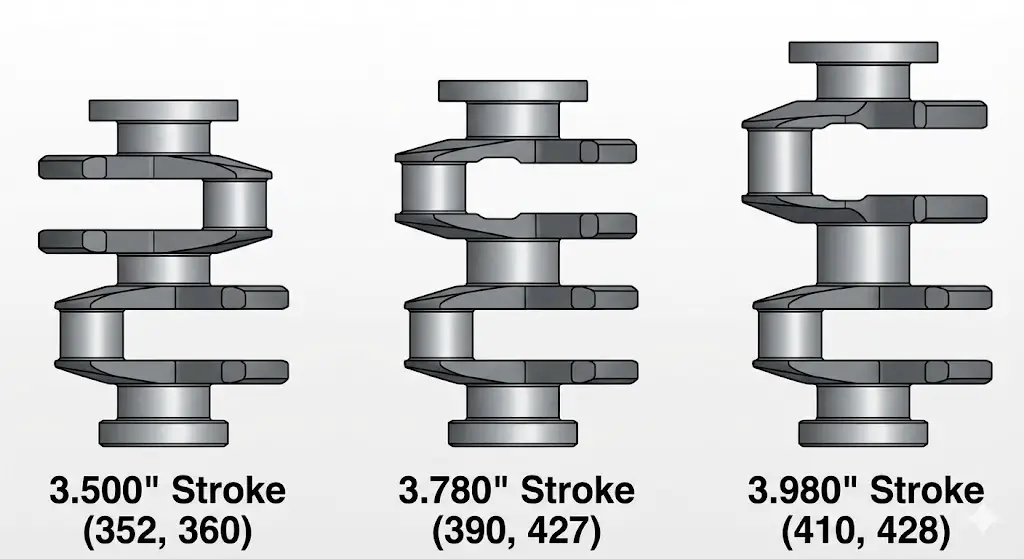

Analytical Insight: The Three Crankshaft Tiers

Analyzing the table reveals that the entire FE legacy is built upon three primary crankshaft strokes. This "parts bin" engineering strategy allowed Ford to react quickly to market trends without retooling the entire production line.

- The 3.500" Foundation (Economy & Utility): The 3.500-inch stroke crankshaft is the bedrock of the early and utility FE engines. It powers the 352, the 360 truck engine, and the 361 variants. Its shorter throw reduces piston speed, making it ideal for the sustained RPMs seen in truck applications or the smooth cruising of early sedans. The transition from the 332 (3.30" stroke) to the 352 was the first indication that Ford intended to grow the engine outward and upward.

- The 3.780" Performance Standard: This stroke defines the golden era of Ford performance. Used in the 390, 406, and 427, the 3.78-inch stroke offers an ideal balance of torque and high-RPM stability. It is worth noting that the 427—Ford's premier racing engine—did not utilize a massive stroke to achieve its displacement. Instead, it relied on a massive 4.23-inch bore. This "oversquare" geometry (bore > stroke) is crucial for racing, as it allows for larger valves and unshrouded airflow while keeping piston speeds manageable at 7,000 RPM.

- The 3.980" Torque Monster: As cars grew heavier in the late 1960s, torque became king. Ford responded by introducing the 3.98-inch stroke crankshaft. When dropped into a 390 block, it created the Mercury 410. When placed in a block with a 4.13-inch bore, it birthed the 428. This long stroke is responsible for the legendary tire-shredding capability of the Cobra Jet, sacrificing some high-RPM breathability for immediate low-end grunt.

Deep Dive: The Passenger Car (FE) Variants

To fully appreciate the FE engine, we must move beyond the numbers and explore the distinct character and evolution of each displacement variant.

The 332 and 352: The First Generation (1958–1960)

The launch of the FE in 1958 was spearheaded by the 332 and 352 cubic inch engines. The 332 was a transient engine, existing only for two years (1958-1959). With its 4.00-inch bore and short 3.30-inch stroke, it was a smooth runner but lacked the torque required for the increasingly heavy Galaxies and Edsels. By 1960, it was dropped, making it a footnote in FE history.

The 352, however, became a staple. Retaining the 4.00-inch bore but increasing the stroke to 3.50 inches, the 352 served as the standard V8 for nearly a decade.

- Performance Peak: In 1960, Ford released a high-performance version of the 352 that produced 360 horsepower. This engine was a technological showcase, featuring an aluminum intake manifold, solid lifters, and streamlined cast-iron headers. It was the first signal that the FE block was capable of serious competition duty.

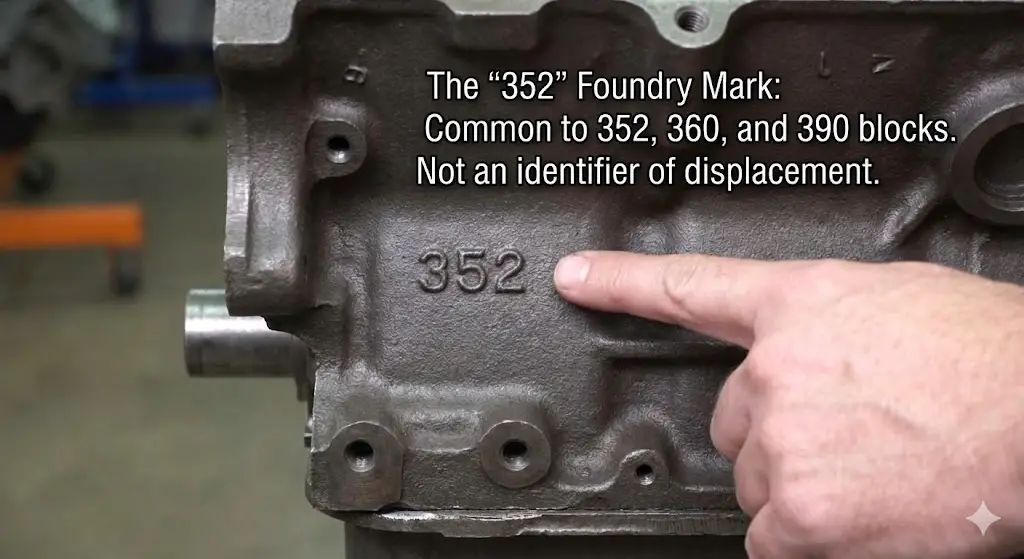

- The "352" Casting Confusion: Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the 352 is the casting number found on engine blocks. For decades, virtually all FE blocks—regardless of whether they were 360s, 390s, or 352s—were cast with the number "352" on the front of the block. This was a foundry mark indicating the engine family, not the displacement. This quirk has led countless enthusiasts to believe they possess a 352 when they may actually have a 390 or 360.

The 390: The Backbone of Ford Performance (1961–1976)

If the 427 is the celebrity of the family, the 390 is the working hero. Introduced in 1961, the 390 increased the bore to 4.05 inches and the stroke to 3.78 inches. It became the most prolific FE engine, powering everything from family station wagons to the Bullitt Mustang.

- 1961-1962 High Performance: The early 390 Hi-Po engines were rated at 375 hp (single 4-barrel) and 401 hp (triple 2-barrel "Tri-Power"). These engines featured higher compression ratios (10.6:1), mechanical valve lifters, and stronger bottom ends.

- The GT Era (1966-1969): The 390 reached its cultural zenith with the introduction of the 390 GT engine in the Mustang and Fairlane. Rated at 320 to 335 horsepower, the GT engine featured specific cylinder heads with a unique exhaust bolt pattern (diagonal and vertical) to accommodate the tight shock towers of the unibody chassis. It also utilized the famous "S" code cast iron intake manifold and a 600 cfm Holley carburetor.

- Decline: By the early 1970s, the 390 was relegated to truck duty. Compression ratios plummeted to the 8.0:1 range to accept unleaded fuel, and net horsepower ratings dropped into the 190-200 hp range. However, the basic architecture remained sound, making these later blocks excellent candidates for rebuilding.

Insight: The 4.05-inch bore of the 390 is widely considered the safe limit for standard FE blocks. While anecdotal evidence suggests some 390 blocks can be bored to 4.13 inches (to replicate a 428), core shift during casting makes this a risky proposition without sonic testing cylinder wall thickness.6

The 406 and 427: Race-Bred Engineering (1962–1968)

As the 1960s progressed, the 390's displacement was no longer sufficient to compete with the 409 Chevys and 413 Mopars on the track. Ford needed more bore.

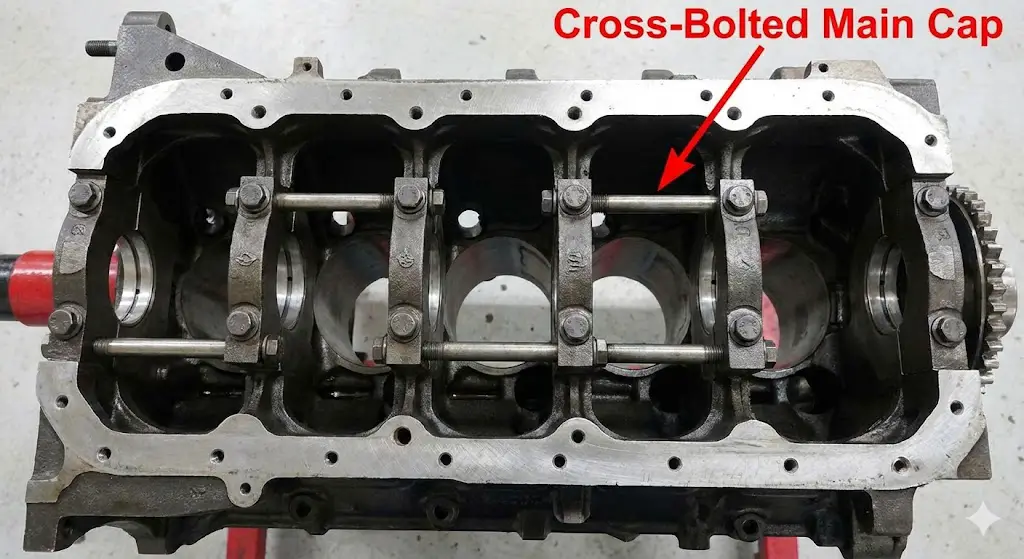

- The 406 (1962-1963): To achieve 406 cubic inches, Ford increased the bore to 4.13 inches. Standard 390 blocks were too thin for this, so a new casting with thicker walls was produced. The 406 also introduced cross-bolted main caps—a racing technology where horizontal bolts go through the side of the block into the main caps to prevent cap "walk" at high RPM. Despite these advances, the 406 suffered from oil starvation in hard cornering, leading to its short lifespan.

- The 427 (1963-1968): The 427 is the crown jewel of the FE line. It maximized the bore to 4.23 inches—the absolute limit of the bore spacing.

- Top Oiler vs. Side Oiler: The early 427s (1963-1964) were "Top Oilers," meaning oil was sent to the camshaft and valvetrain first, then to the main bearings. This was adequate for drag racing but risky for endurance racing like Le Mans. In 1965, Ford introduced the "Side Oiler" block. This design featured a dedicated oil galley cast into the side of the block (visible as a bulge on the exterior) that prioritized oil delivery to the main bearings and crankshaft before the valvetrain. This ensured that the bottom end survived the rigors of 24-hour endurance races.

- The 427 SOHC "Cammer": In a bid to dominate NASCAR, Ford developed a version of the 427 with Single Overhead Cam (SOHC) hemispherical heads. Although banned by NASCAR, the "Cammer" became a legend in drag racing, producing over 600 horsepower in factory trim.

The 428 Cobra Jet: Power for the People (1966–1970)

The 427 was expensive to build and required meticulous maintenance, making it unsuitable for mass-market muscle cars. Ford needed a cheaper, more streetable big block. The answer was the 428.

- The Formula: Ford took the 4.13-inch bore of the 406 and combined it with a longer 3.98-inch stroke crankshaft. The result was 428 cubic inches of torque-biased displacement.

- Cobra Jet (CJ): Introduced in April 1968, the 428 Cobra Jet became an instant legend. It utilized 427 "Low Riser" style cylinder heads with larger valves (2.09" intake / 1.65" exhaust) and a 735 cfm Holley carburetor. Ford famously underrated it at 335 horsepower to appease insurance companies, but dyno tests consistently showed it producing closer to 400 horsepower.

- Super Cobra Jet (SCJ): For drag racers, Ford offered the Super Cobra Jet. This package included the "Drag Pack" option (3.91 or 4.30 rear gears) and featured internal upgrades for durability. The SCJ used heavier "Cap Screw" connecting rods (unlike the nut-and-bolt rods of the CJ) and an external oil cooler. Crucially, the heavier rods changed the reciprocating mass, requiring the SCJ to be externally balanced with a specific counterweight on the harmonic balancer and a "hatchet" weight on the crankshaft spacer.

The Industrial Workhorses: FT (Ford Truck) Engines

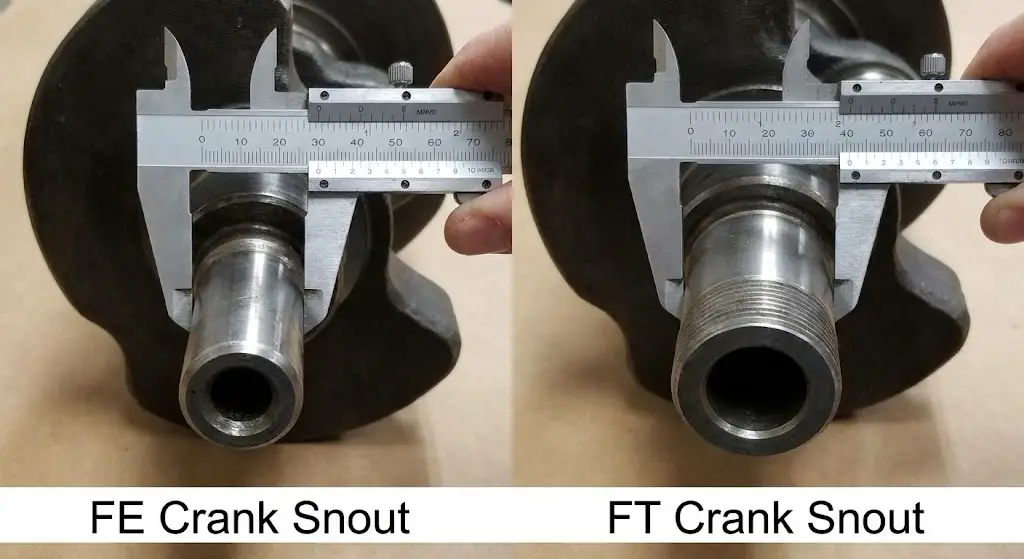

While the FE engines were winning races, their heavy-duty siblings, the FT engines, were hauling freight. Found in medium and heavy-duty trucks (F-500 through F-900), the FT series shares the basic architecture of the FE but differs significantly in component design to prioritize durability over horsepower.

The 330 MD and HD

The 330 cubic inch engine was the entry-level FT. It came in two flavors:

- 330 MD (Medium Duty): Utilizing a 3.875" bore and 3.50" stroke, the MD shared many components with the smaller FE engines, including the crankshaft snout size.

- 330 HD (Heavy Duty): The HD version used the same dimensions but featured a forged steel crankshaft with a larger snout, heavy-duty heads, and a deep-sump oil pan. The 3.875" bore is unique to the 330 and requires specific head gaskets.

The 361 and 391

The larger FT engines mirrored the displacements of their passenger car cousins but with heavy-duty modifications.

- 361 FT: Shares the 4.05" bore and 3.50" stroke with the FE 360.

- 391 FT: Shares the 4.05" bore and 3.78" stroke with the FE 390.

- The "Mirror 105" Block: Many 391 FT blocks were cast with high-nickel iron content for strength. These blocks often feature the number "105" cast in a mirror image on the front face. Engine builders prize these blocks (specifically the D3TE castings) because they often have thicker cylinder walls and reinforced main webs, making them excellent candidates for high-performance stroker builds, provided the necessary machining is done to the distributor pilot hole.

Critical Differences: FE vs. FT

Interchanging parts between FE and FT engines is a common pitfall. The following table highlights the incompatibilities.

Table 2: FE vs. FT Interchangeability Matrix

| Component | FE (Passenger/Light Truck) | FT (Medium/Heavy Truck) | Compatibility Notes |

| Crankshaft Snout | 1.375" Diameter | 1.750" Diameter | FT cranks generally do not fit FE timing covers without machining. |

| Distributor Pilot | 1/4" Hex Shaft | 5/16" Hex Shaft | FT distributors have a larger shaft and gear; they do not fit FE blocks without bushing modification. |

| Exhaust Manifold | 8 Bolts (Vertical pattern) | 10 Bolts (Center crossover) | FT heads utilize a central exhaust crossover port that does not align with FE manifolds. |

| Water Pump | Standard FE Pattern | High-mount, different bolt pattern | FT water pumps and pulleys are incompatible with FE brackets. |

| Flywheel Balance | Internal (mostly) | External (heavy counterweights) | FT flywheels are balanced differently and cannot be used on internal balance FE engines. |

Identification: Decoding the Castings

Identifying an FE engine in the wild can be notoriously difficult due to Ford's ambiguous casting practices.

The "352" Block Casting Myth

As mentioned, the vast majority of FE blocks feature the number "352" cast onto the front driver's side of the block. This does not indicate displacement. It is a generic foundry mark. A block marked "352" could be a 352, a 360, a 390, or even a 410. The only way to definitively identify the displacement of an assembled engine is to measure the stroke (using a dowel in the spark plug hole) and the bore (if the head is off).

Key Casting Numbers to Watch For

While the "352" mark is generic, specific casting numbers located on the passenger side of the block can provide clues.

- C6ME-A: A universal block casting used from 1966 onwards. It can be found on 390s, 410s, and 428s. If you find this block, you must check the cylinder walls. Some were drilled for hydraulic lifters, some were not.

- C5AE-H: This is a specific casting often associated with the 427 Side Oiler. Look for the characteristic "bulge" on the side of the block and the cross-bolted main caps.

- D3TE: A late-model truck block (1973+). These are robust castings often found in 360s and 390s. They feature reinforced webbing and are highly desirable for performance builds.

Performance Building: Unlocking the Potential

The FE engine is currently enjoying a renaissance in the restomod community. Modern technology has resolved many of the platform's quirks, allowing builders to extract massive power.

The "Poor Man's 427": The 445 Stroker

Since original 427 and 428 blocks are rare and expensive, the most popular route to big displacement today is the "stroker" 390.

- The Recipe: Take a standard 390 block (4.05" bore) and install an aftermarket crankshaft with a 4.25" stroke.

- The Result: This combination yields 445 cubic inches. With modern aluminum cylinder heads (such as those from Edelbrock or Trick Flow), this combination easily produces 500+ horsepower and 500+ lb-ft of torque, all while fitting under a standard hood.

Solving the Oiling Issues

The FE's oiling system has a reputation for being problematic at high RPM, primarily due to the restrictive oil passages in the block that feed the cam bearings first (in Top Oilers).

- The Fix: Modern builders restrict the oil flow to the rocker arms. The factory system sends significantly more oil to the top end than is necessary for modern valve springs and lifters. By installing a restrictor (often a Holley carburetor jet) in the oil feed passage to the heads, builders keep more oil pressure in the main and rod bearings where it is needed most.

- Gallery Plugs: Another critical modification involves removing the factory press-fit oil gallery plugs and replacing them with threaded pipe plugs. The press-fit plugs have been known to pop out under high pressure, causing catastrophic oil pressure loss.

Intake Manifold Selection

The FE intake manifold is massive, extending under the valve covers to form part of the head sealing surface.

- Weight: A stock cast-iron 4-barrel intake weighs nearly 80 lbs. Swapping to an aluminum aftermarket intake is one of the most effective ways to shed weight from the front of the car.

- Port Matching: It is crucial to match the intake manifold to the cylinder heads. FE heads come in "Low Riser," "Medium Riser," "High Riser," and "Tunnel Port" configurations. A High Riser intake will not seal correctly on Low Riser heads, leading to massive vacuum leaks.

Conclusion

The Ford FE engine family stands as a monument to mid-century American engineering resilience. Born from the need to power heavy sedans, it evolved into a racing dynasty that conquered the world's most prestigious tracks. For the modern enthusiast, the FE offers a unique blend of history and performance potential. By understanding the nuances of the bore and stroke combinations detailed in this chart, identifying the correct casting numbers, and applying modern building techniques, one can preserve this legacy while enjoying horsepower levels that the original engineers could only dream of.

Whether you are performing a concours restoration on a 1968 Shelby GT500 or building a 445 stroker for a 1970 F-100, the FE engine remains one of the most rewarding platforms in the classic car world. Its deep skirt block, massive potential for displacement, and roaring soundtrack ensure that the "Ford-Edsel" engine will never be forgotten.